- Latest News

- Ocean Conferences

- Science: Explained

What is the High Seas Treaty?

Everything you need to know about the High Seas Treaty

Officially, it is the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction. It is known colloquially as the High Seas Treaty. Or, BBNJ (biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction) Agreement.

It will enters force on 17 January 2026, 120 days after receiving the necessary 60 ratifications on the 19 September 2025.

What are the high seas?

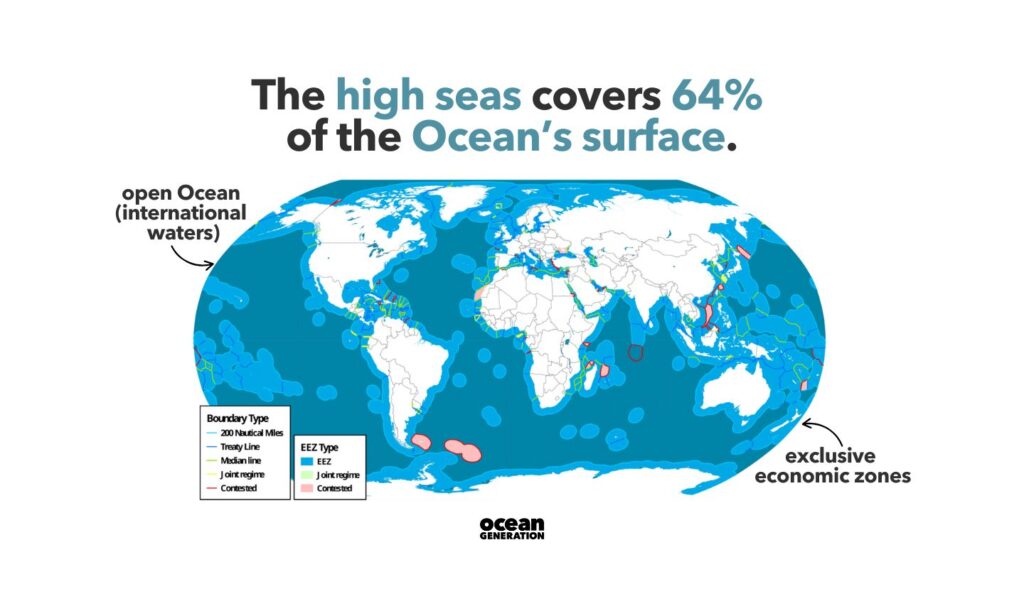

The high seas refer to around 64% of our Ocean’s surface.

In 1958, 63 countries signed the Convention on the High Seas, defining the “high seas” as the Ocean not within territorial waters.

In 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was signed, establishing exclusive economic zones (EEZs) reaching 200 miles out to sea– each country has sovereign rights (‘ownership’) to the Ocean and seabed within 200 miles of its coast.

The rest of the Ocean, including the water column and “the Area” (the seabed outside these EEZs), are the high seas.

What does the treaty do?

- Enables the creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) on the high seas – outside of national waters.

- Requires nations to conduct environmental impact assessments before marine activity.

- Mandates the sharing of marine genetic resources and digital sequence information sourced from areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) between Parties (countries included). This includes monetary and non-monetary benefits.

- Share marine technologies between Parties, including funding mechanisms. This is aimed to enable developing nations to contribute to and benefit from Ocean conservation.

What is the process?

The agreement can be traced back to December 2017, when the United Nations General Assembly voted to start creating the High Seas Treaty.

The agreed-upon five meetings (with a gap due to COVID-19) failed to produce an agreement.

In March 2023, at the sixth meeting, the text of the agreement was finalised. The treaty was open for signatures for two years, from 20th September 2023, until 20th September 2025.

68 countries immediately signed the agreement, and another 13 signed in the two days after.

Palau was the first country to ratify, in January 2024.

At the United Nations Ocean Conference in June 2025, there were 20 signatories and 19 countries ratified, bringing the total number to 51.

What’s the difference between signing and ratifying?

Signing the agreement and ratifying are not the same. Signing is announcing the attention to ratify. Ratifying the agreement means committing to the agreement officially.

There is no deadline on ratification after signing; Parties can ratify at any point. Only Parties that have ratified the treaty are legally bound by it, and able to enjoy the benefits.

When did the High Seas Treaty come into force?

On 19 September 2025, Morocco became the 60th country to ratify. This initiated a 120 day countdown, which ended on January 17th 2026. From then, it is legally binding (for those who have ratified).

A year on, the first Conference of the Parties (COP) will meet to discuss high seas conservation, such as identifying the areas to protect. Belgium and Chile have submitted bids to host the Secretariat, and Chile has included a suggestion for the first high seas MPA.

Why protecting the high seas is so important

The high seas used to be out of our reach. Untouchable and unaffected by human activities. But in just the last sixty years or so, our technology has improved, this vast wilderness has become far less wild.

This has enabled us to benefit from the Ocean beyond our national borders. Fishing flotillas can travel the world and cargo ships cris-cross the Ocean. This global reach – impossible to our grandparents – has changed our relationship with the Ocean.

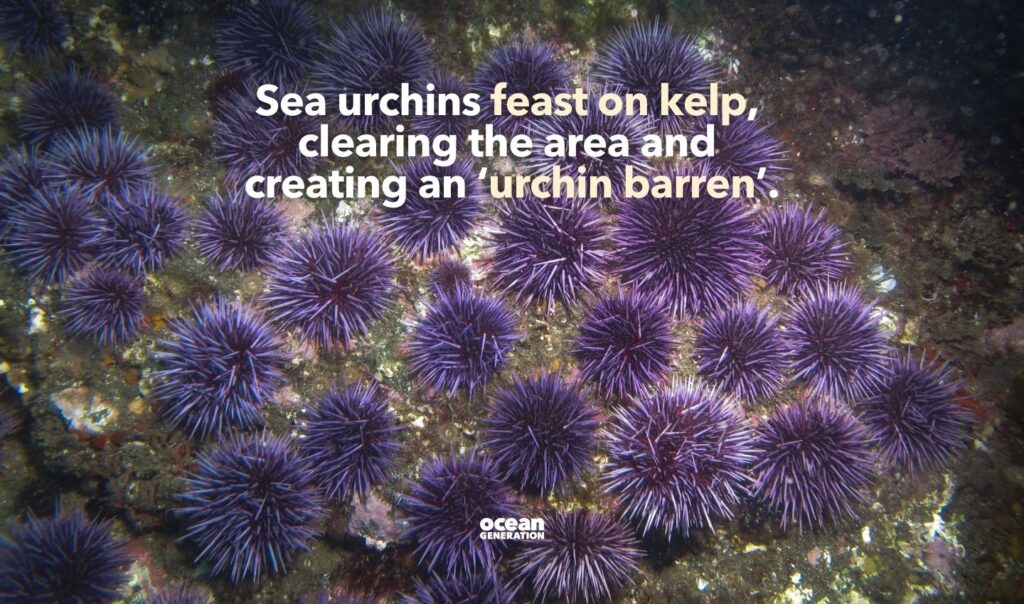

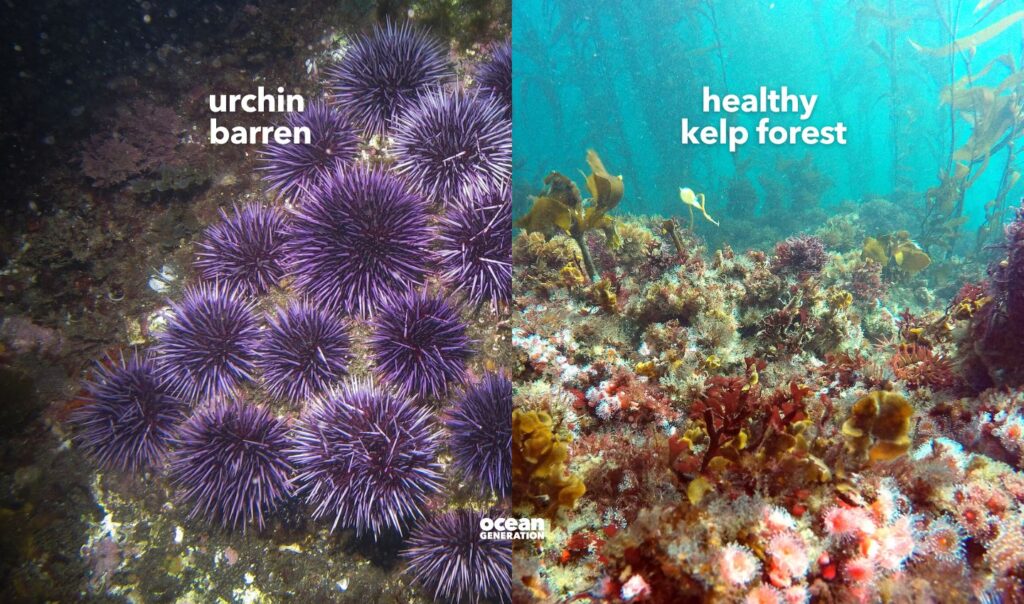

Without responsibility or ownership over the high seas, everyone has an incentive to extract as much as they can before anyone else. In just six decades, this free-for-all has led fishing stocks being depleted, marine animals being exposed to large amounts of noise from marine traffic and pollution accumulating out at sea.

The High Seas Treaty aims to solve this and enables the protection of important marine areas that don’t belong to any single nation. It enables the world to take responsibility for the wild Ocean.

A common misconception is that the end goal of conservationists and the marine industry (such as fishing and tourism) are incompatible. But healthy fish stocks are all a fisherman asks for, flourishing ecosystems pull in tourists and rich biodiversity offers untold discoveries and advances in pharmaceuticals and engineering to name but two.

Protecting the Ocean means letting it thrive, and we all enjoy the boon of a thriving Ocean.

The High Seas Treaty creates an opportunity. An opportunity to nurture our Ocean and share the benefits from it.

Ocean Generation’s Statement on the High Seas Treaty:

“We are delighted to hear that the UN High Seas Treaty has finally become a reality.

A healthy Ocean is vital for the survival of all living things, and this is the message we continue to deliver through our work at Ocean Generation. Protecting 30% by 2030 must, however, be seen as a minimum requirement.

We view this agreement as a starting point. The Ocean is our ally in the fight against climate change and we must stop underestimating its role in our survival.”

Jo Ruxton MBE

Founder of Ocean Generation