- Science: Explained

How can we protect and restore our coastlines?

Coastlines are the gateway to the Ocean.

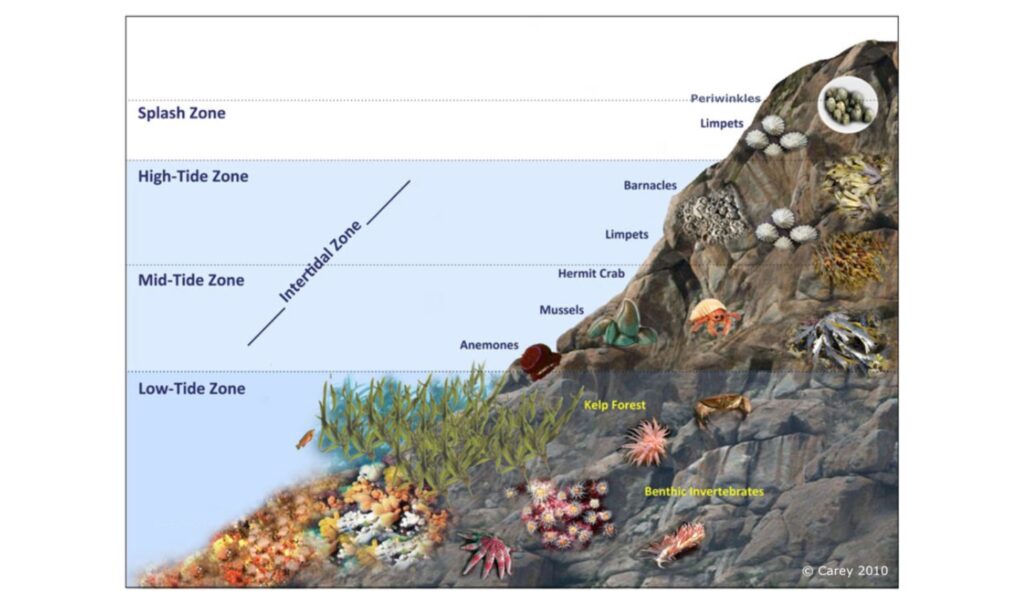

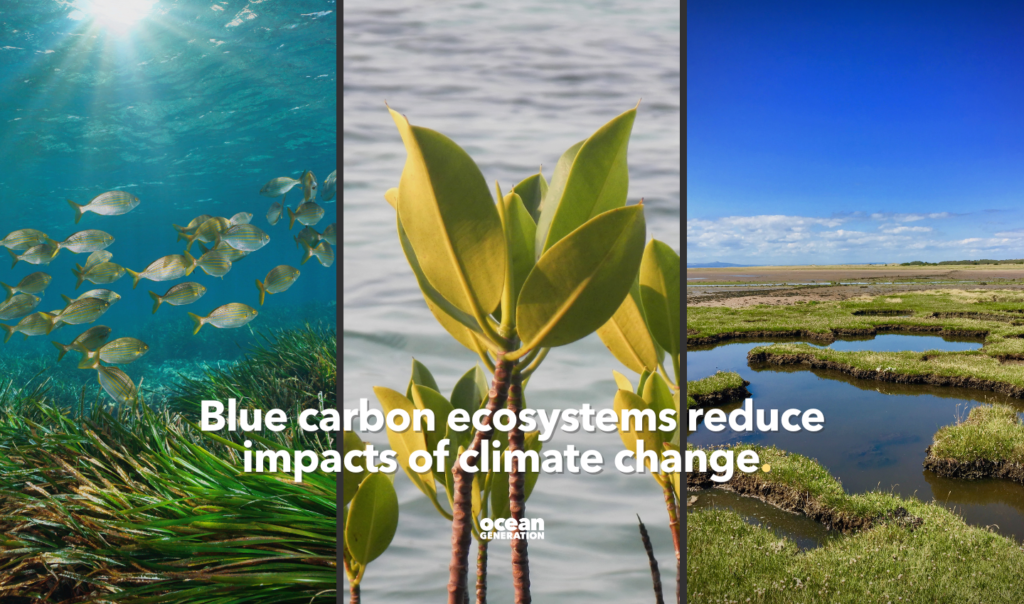

Vital ecosystems like mangrove forests, seagrass meadows, coral reefs and tidal marshes exist almost exclusively in coastal regions.

They support a high biodiversity of life and provide key nursery and breeding areas for migratory species.

They’re also essential to the livelihoods of coastal populations, and we all rely on the important services they provide, such as carbon sequestration and protecting the coast from erosion.

Our coastlines are under threat.

If you’re wondering which of the five key Ocean threats impact our coastlines, the answer is all of them.

Because coastlines are the boundary between land and sea, our impacts are often amplified in coastal regions due to their proximity to the cause…us.

With more than one third (2.75 billion) of the world’s population living within 100km of the coast, it’s no surprise that coastal regions are heavily concentrated.

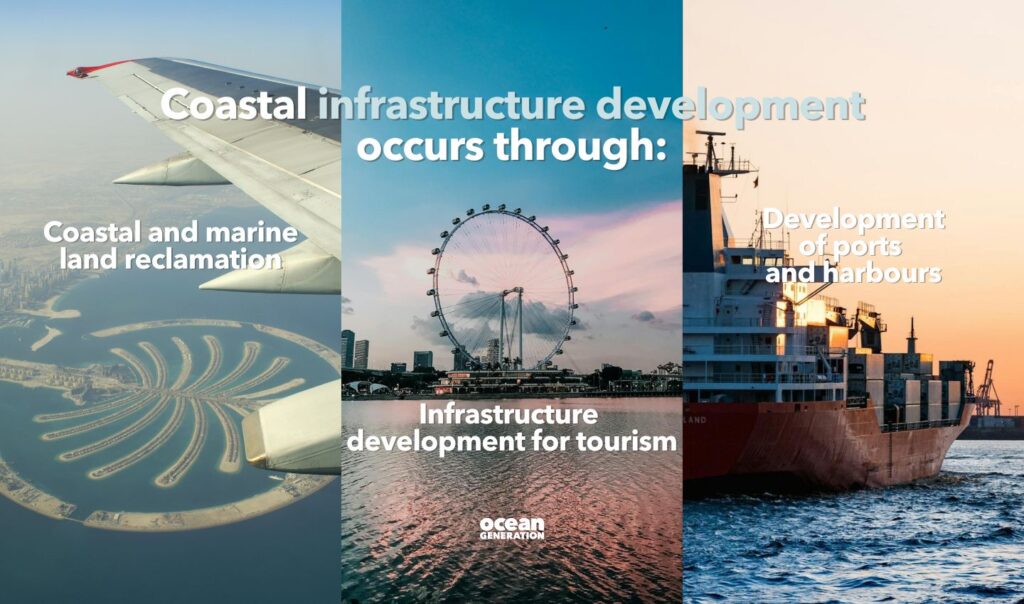

To supply the needs of this ever-growing population, coastal infrastructure development happens through:

- Coastal and marine land reclamation, the process by which parts of the Ocean are formed into land.

- Infrastructure development for tourism, such as resorts and recreational facilities.

- Development of ports, harbours, and their management.

This is a key driver for habitat destruction (when a natural habitat can no longer support the species present) and biodiversity loss. It also increases the vulnerability of coastal communities to climate change impacts.

With higher frequencies of natural events like cyclones and hurricanes, risk of erosion, saltwater intrusion, flooding and other cascading climate change impacts, coastal regions have never been this vulnerable.

How can we protect and restore our coastlines?

Enter: Nature Based Solutions (NBS). These are described by the IUCN as:

‘Actions to protect, sustainably use, manage and restore natural or modified ecosystems, which address societal challenges (such as climate change, food and water security) effectively and adaptively, while simultaneously providing human-wellbeing and biodiversity benefits.’

In other words, when we protect and restore natural ecosystems, we provide a whole host of benefits to ourselves, too.

This can be done by restoring degraded ecosystems to their former glory and halting further loss of existing ecosystems.

Ocean Solution: Habitat restoration.

Habitat restoration is the process of actively repairing and regenerating damaged ecosystems.

Restoring coastal ecosystems such as mangrove forests, coral reefs, oyster beds and seagrass meadows allow us to address environmental challenges (such as biodiversity loss). It reduces risks to vulnerable communities (like flooding, erosion, and freshwater supply). It also contributes to sustainable livelihoods by providing job opportunities.

That’s why at Ocean Generation, we support a mangrove restoration project in Madagascar, led by Eden Reforestation.

In 2022 alone, this project contributed to:

- Carbon sequestration and habitat restoration by planting over 4.3 million young mangrove trees.

- Creating sustainable livelihoods by employing around 70 people per month at the Maroalika site, with a total of 1,468 working days generated over the year.

PSA: We plant a mangrove for every new follower on Instagram and newsletter subscriber. Sign up to our newsletter or follow us on our socials to be part of the change today.

Ocean solution: Marine Protected Areas.

To halt ecosystem destruction and prevent further habitat loss, we must take measures to protect remaining coastal ecosystems.

One mechanism to achieve this is by implementing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). These are designated areas of the Ocean established with strict regulations to protect habitats, species and essential processes within them.

If implemented and monitored effectively, Marine Protected Areas can provide a range of benefits across biodiversity conservation, food provisioning and carbon storage

What is the 30 by 30 target?

In recognition of the importance of healthy and thriving ecosystems, the Global Biodiversity Framework have established a “30×30” target. This calls for the conservation of 30% of the earth’s land and sea through the establishment of protected areas by 2030.

Spoiler alert: We’re not on track to meet this goal.

According to the Marine Protection Atlas (2024), only around 8% of the global Ocean area has been designated or proposed for MPAs, and only 2.9% of the Ocean is in fully or highly protected zones.

Research also shows that 90% of the top 10% priority areas for biodiversity conservation are contained within coastal zones (within 200-miles of the shore). We must ramp up our efforts to preserve these vital coastal ecosystems and ensure that MPAs continue to benefit both people and planet.

What are the main challenges to implementation?

Over the past 10 years, interest in the potential of Nature Based Solutions to help meet global climate change and biodiversity goals has surged, as we have begun to truly appreciate the importance of natural ecosystems.

Despite this knowledge and an abundance of opportunities for implementation worldwide, marine and coastal regions still lack uptake.

We must address the barriers to implementation to accelerate the rate of success of coastal protection worldwide, including (but not limited to):

- Conflict of interest between stakeholders i.e. blocking of protective legislation by fishing and other extractive industries.

- Marine and coastal ecosystems are ‘out-of-sight, out-of-mind’. This results in a lack of public and policy awareness of their value. As a result, Nature Based Solutions are often overlooked in favour of grey infrastructure such as seawalls.

Increasing our understanding of the vital services provided by coastal ecosystems is critical to overcoming these barriers.

The more we appreciate what these incredible ecosystems do for us, the more likely we are to succeed in protecting and restoring our coastlines.