- Voices of the Ocean

Citizen science: Monitoring the turtles of the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a storied body of water that many have heard of, but few are familiar with.

Its history will bring up names like Hatshepsut and Moses, and its present is fraught with tales of piracy and political unrest.

But there’s another side to the Red Sea. As the most northern tropical sea, it boasts an incredible biodiversity that makes it both stunningly beautiful and ecologically vital.

I had the pleasure of spending two weeks with TurtleWatch Egypt 2.0, an organisation dedicated to monitoring the endangered sea turtle populations of Egypt’s Red Sea coast.

They launched as an initiative in 2011, and registered as an NGO in 2022. I was curious to learn more about marine conservation in my home country. To my luck, TurtleWatch was the perfect place to start.

Based in the small town of Marsa Alam, their day-to-day work may be a dream for many thalassophiles.

Mornings are spent diving in bays rich with seagrass and corals, snapping photos of sea turtles and measuring data like shell length and water temperature.

Of course, their work has less idyllic parts too. Never-ending paperwork, grant applications, and database updates are just as important to the organisation’s functioning.

There’s one other thing that makes TurtleWatch especially unique: citizen science.

They were the first initiative in Egypt aimed at involving divers and snorkelers in marine conservation research.

How? By allowing visitors to the Red Sea to upload their own sightings and pictures of sea turtles, TurtleWatch taps into the potential of everyday people to contribute as citizen scientists.

These contributions help TurtleWatch identify important feeding and gathering sites for sea turtles, and better understand their movements and short-term migrations. It also helps them assess the impacts people have on these endangered animals.

They use this information to not only improve conservation and protection efforts, but to organise training sessions for dive centres and deliver “turtle talks” to young children, students, and tourists.

Citizen science is not a new concept.

It has been used around the world to classify galaxies and track illegal fishing. But in a place like the Red Sea, which is understudied and where data is insufficient, TurtleWatch has managed to greatly extend their eyes and ears beyond their local vicinity.

Sightings come from all over the coast, and in 2023 they received over 1000 sightings.

It makes perfect sense: Egypt’s Red Sea coast is filled with towns and resorts buzzing with snorkelers and divers, so why not involve them in the effort to protect the very marine life they’ve come here to enjoy?

As with everywhere else, the Red Sea hasn’t escaped the destructive impacts of people on the natural world.

Coastal development and tourism are polluting the marine environment and leaving physical scars, while warming waters and acidification are harming the Red Sea’s ability to withstand changes.

The good news is that corals in the Red Sea are some of the most resilient on the planet and could help us protect other corals reefs in the future.

But before that’s possible, we will need better regulations and more marine protected areas to safeguard the Red Sea.

Organisations like TurtleWatch—with the aid of citizen science—are doing their part to provide much-needed data and help protect this beautiful sea for future generations.

Thank you for raising your voice for the Ocean, Serag!

Connect with Serag Heiba via LinkedIn. Learn about how to submit your own Wavemaker Story here.

Disclaimer: Ocean Generation has no official affiliation with TurtleWatch. Mention of or reference to TurtleWatch is not an endorsement or sponsorship by Ocean Generation. The views, opinions, and activities of TurtleWatch are independent of Ocean Generation.

![Katie, a Wavemaker shares this quote: My faith in the [...] next generation of changemakers gives me hope for the future of our marine and coastal ecosystems.](https://oceangeneration.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/next-generation-of-changemakers-gives-hope-for-marine-ecosystems-1024x604.jpg)

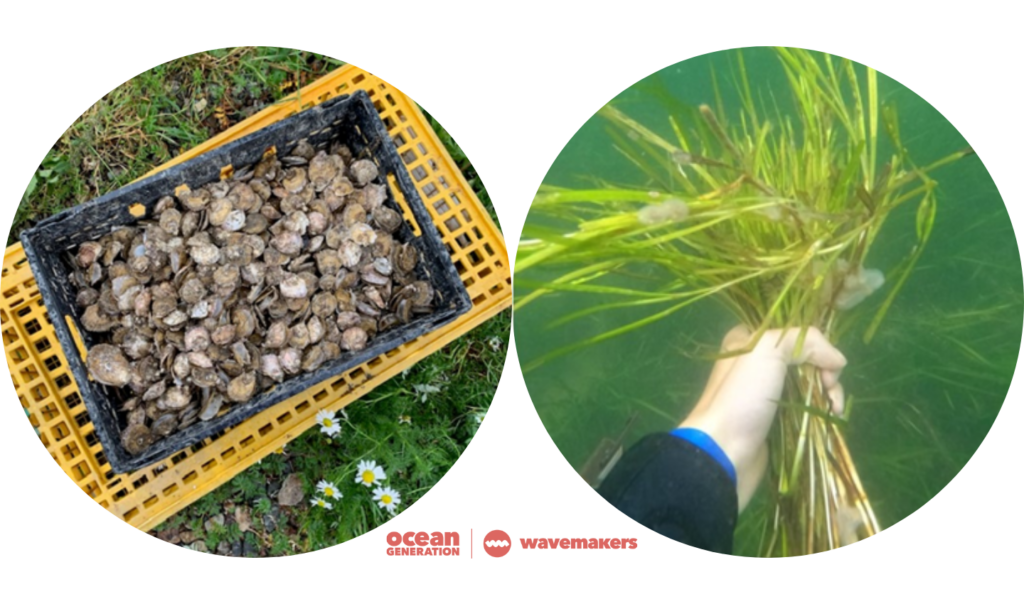

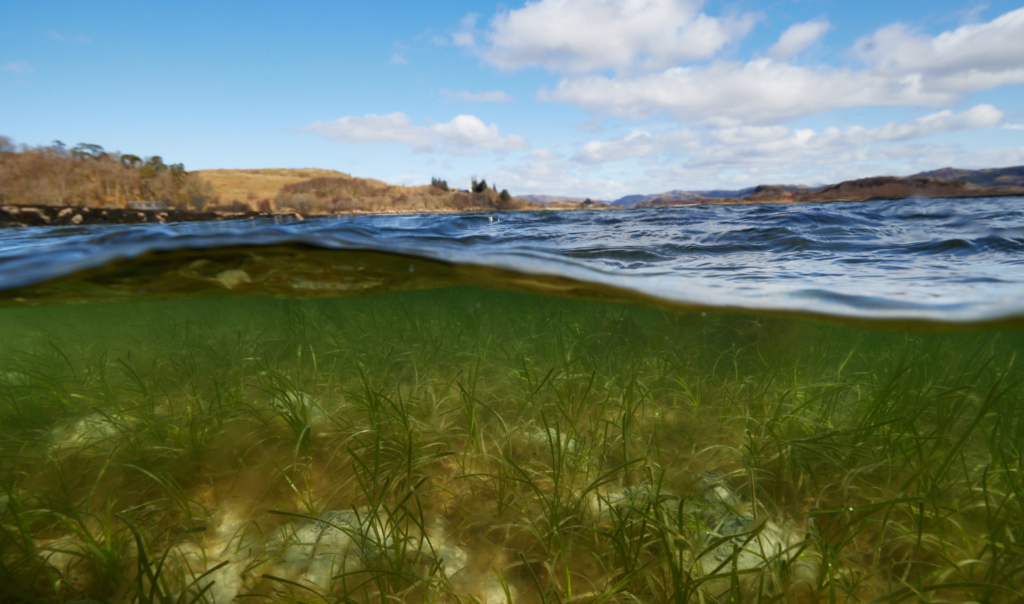

![Woman diving into the Ocean shared by Ocean Generation in a Wavemaker Story. There's a quote that reads: I spent my summer [...] restoring seagrass meadows and native oyster reefs. Photo by Sophie Coxton.](https://oceangeneration.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/community-led-marine-habitat-restoration-organisation-Scotland-restore-seagrass-meadows-and-native-oyster-reefs-1024x604.jpg)