- Latest News

- Ocean Conferences

- Science: Explained

7 Ocean wins from COP27

Everything you need to know: COP27 outcomes.

COP27 was the third longest COP in history – but what Ocean and planet wins did the global climate summit deliver?

One things was strikingly clear throughout COP27: Climate change has become mainstream.

Global coverage of the biggest climate summit made headlines through the weeks, providing hope or despair, depending on where you looked.

What was the biggest win at COP27?

The push for stronger climate financing measures resulted in the historic outcome of establishing a ‘loss and damage fund’. Although the finer details hadn’t been drafted at the end of the climate conference, this was still the prominent highlight of COP27.

This fund will only be available for developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate-related disasters. This is a crucial win for small island nations.

What is loss and damage, in the context of climate conversations?

In a COP27 interview, Dr. Kees van der Geest, Senior Migration Expert, United Nations University, Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS), explained what loss and damage means in a nutshell:

“I’ve been working on it [loss and damage] for 10 years. ‘Loss and damage’ is really about situations; where people live in places where the impacts of climate change are so severe that adaptation is no longer possible or feasible. It is not necessarily a future scenario because that is the lived reality for some people now.”

Read: Here’s an article about the loss and damage fund established at COP27 for further reading.

What was the biggest disappointment of COP27?

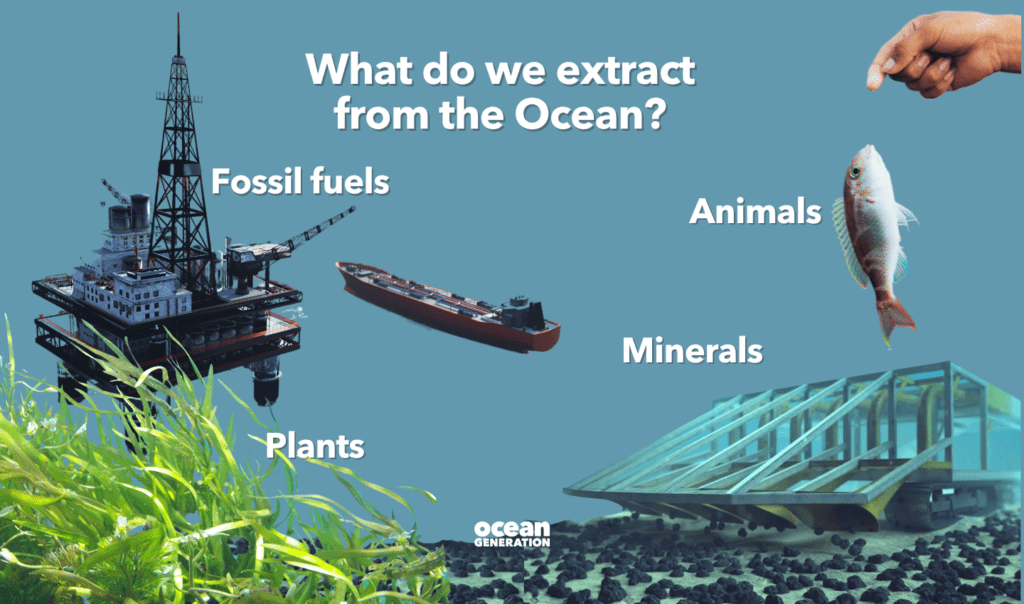

With global warming at 1.1C, COP27 proved that the scientific consensus of limiting warming to 1.5C was not being taken seriously enough. The final decision made no mention of phasing down fossil fuels, except for coal, with the power of fossil fuel delegates tremoring through this decision.

The IPCC (a kind of survival guide for humanity) stresses that global emissions must decline 45% by 2030. If we want to keep this limit alive, we need to peak global emissions by 2025.

This does not mean that we should just wait until COP28 in hopes of sweeping action.

In every corner of the world, people are rallying together to implement ambitious initiatives and COP27 has also shed light on many positive developments.

For people and the planet.

And the Ocean!

Seven Ocean wins from COP27:

1. Young people are part of the decision-making progress.

COP27 hosted a Youth and Children Pavilion, marking the first official space for young people at a COP.

Another milestone came from YOUNGO, the official children and youth constituency of the UNFCCC, being recognised as stakeholders in designing and implementing climate policies.

2. Enthusiasm for the energy transition.

Despite the disappointment with curbing fossil fuels, the enthusiasm for a just energy transition is undeniable. Renewable energies are here to stay.

Some of the renewable energy transition commitments include:

- Tanzania updated their NDC to achieve 80% adoption of renewable energies by 2025 (from 60% in 2015).

- The Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia which launched at the G20 summit, in parallel to COP 27, will secure $20 billion from wealthy economies to scale up renewables like solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal.

3. The Global Methane Pledge gains momentum.

In the first week of COP27, we shared that 130 countries has joined the Global Methane Pledge. By the end of COP27, that number grew to 150 countries.

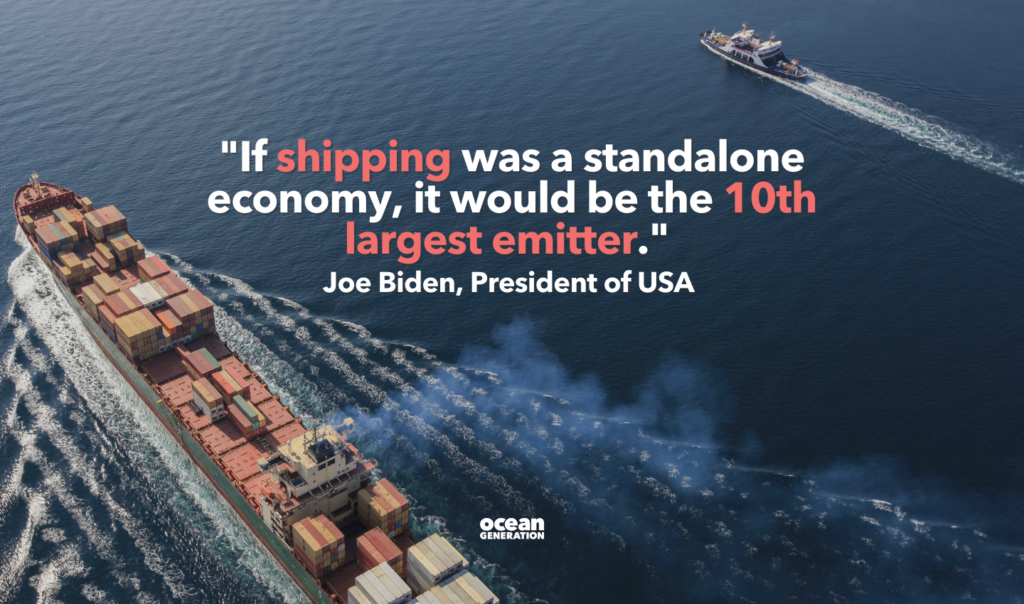

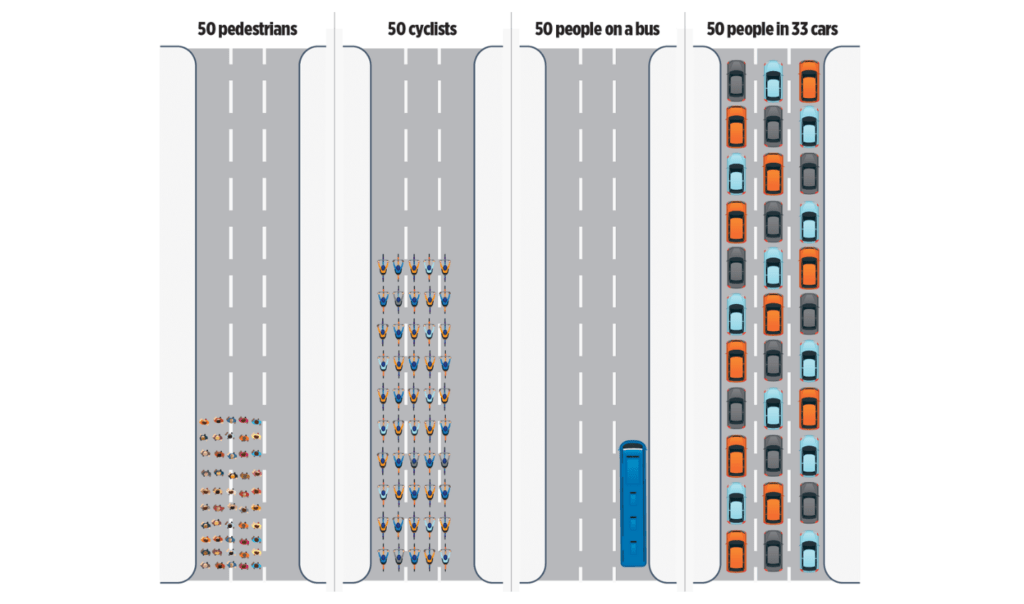

4. Decarbonising the shipping industry is a serious priority.

There has been massive mobilisation to curb shipping emissions.

Some of the measures include:

- More countries, ports and companies stated their plans to support the Green Shipping Challenge. Here’s a list of the various announcements made.

- The EU’s “Fit for 55” package proposal includes the first ever carbon market for shipping and adoption of cleaner fuels.

- Noteworthy policy recommendation: No one country is responsible for a majority of shipping emissions but a study conducted by Transport & Environment showed that a zero-emission mandate in EU, China, and US could decarbonise 84% of global shipping.

5. The Ocean is part of the final COP27 cover decision.

In 2022, the Ocean had a seat at climate conversations at COP27.

The importance of Ocean-based climate action was highlighted and the COP27 cover decision emphasised this need and encouraged nations to “blue” their NDC’s.

6. Funds will be made available for early-warning systems.

Vulnerable nations need early-warning systems for adaptation and building resilience. UN Secretary-General António Guterres announced a $3.1 billion plan to support the development of these systems to protect people within the next five years.

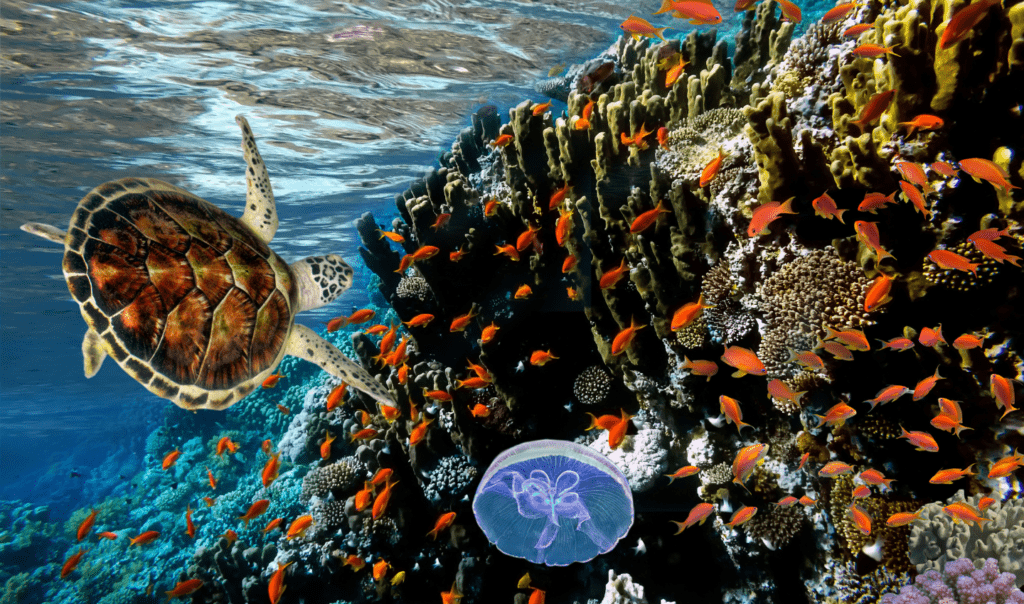

7. Spotlight on nature-based Ocean solutions.

We cannot address climate change without considering the Ocean.

As more people realise this, we’re seeing great initiatives that support protecting the Ocean and ensuring its health:

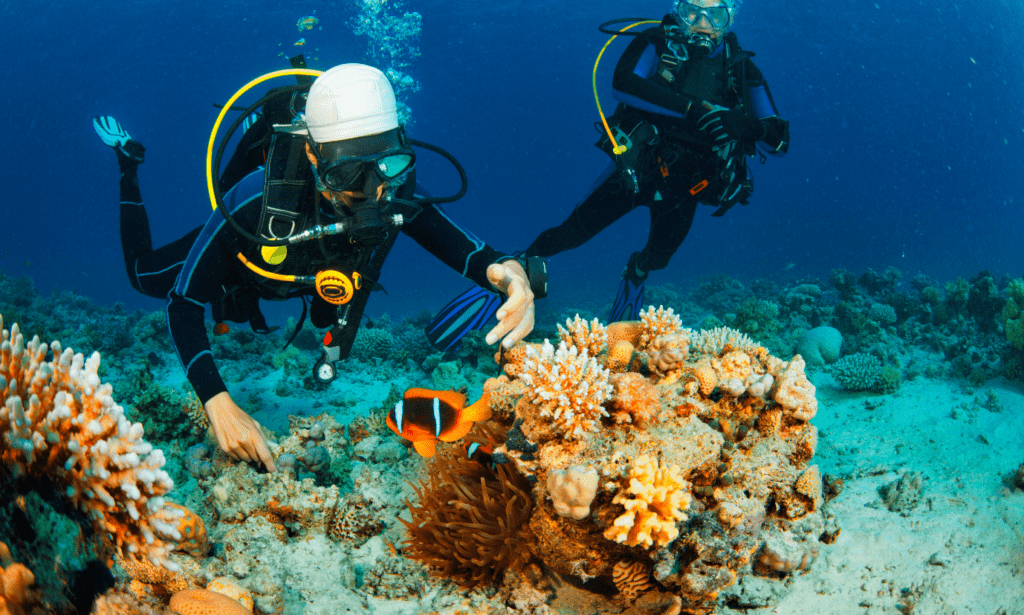

- The Great Blue Wall Initiative aims to protect marine areas to counteract the effects of climate change and global warming.

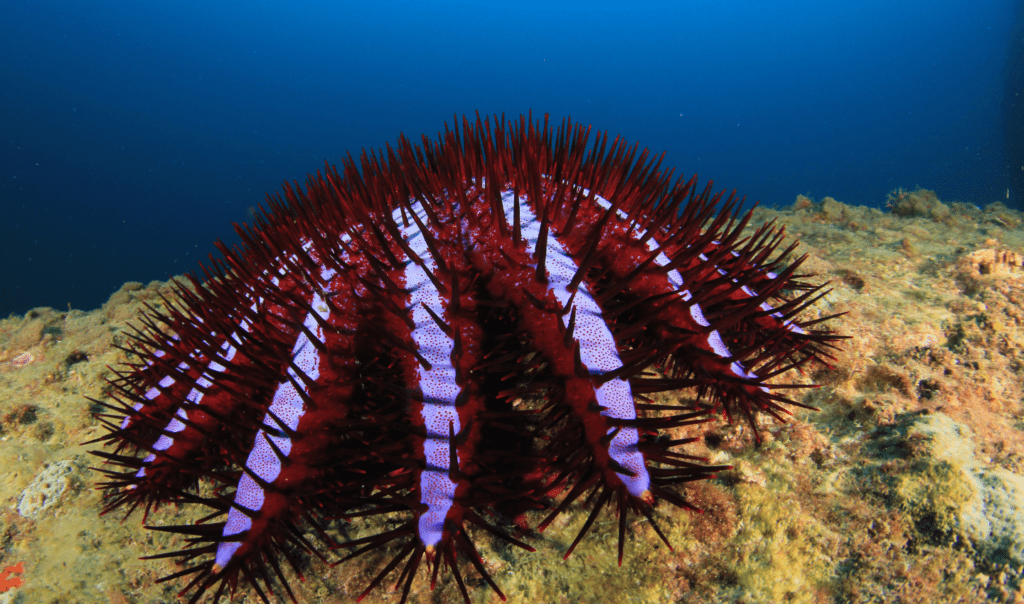

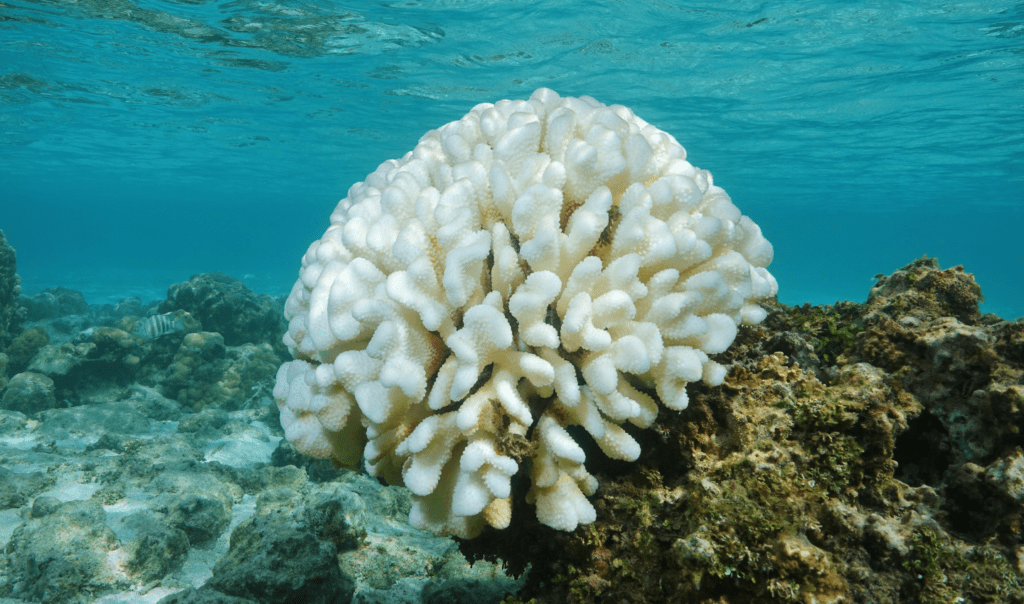

- Hope for Coral Reefs – Egypt announced protection for the entire Great Fringing Reef in the Red Sea, creating a 2000km marine protected area (MPA).

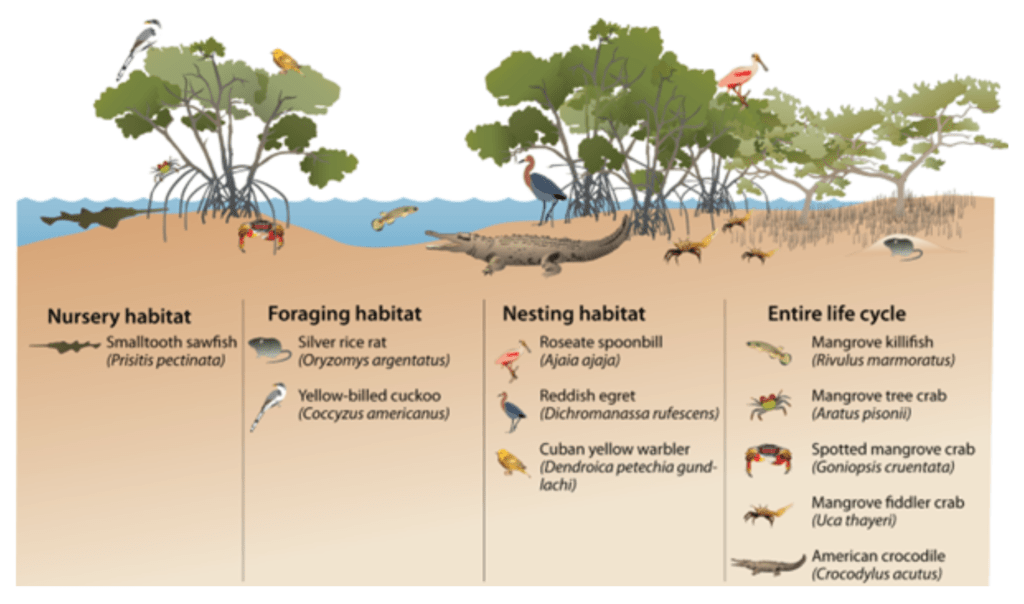

- The Mangrove Breakthrough Alliance aims to secure the future of 15 million hectares of mangroves globally, by 2030, through collective action.

- The Convex Seascape Survey is a research programme aiming to provide critical data and insights on the connections between carbon and the Ocean.

“The Ocean and nature are our greatest allies to mitigate and adapt to climate change, as conservation efforts have a “triple bottom line” in that they address economies, communities, and nature.”

Razan Al Mubarak, President, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

Ocean Generation’s comment on COP27:

Like any other COP, there is always going to be tension between progress and potential setbacks.

While there will always be room for doing more and better, COP is the only summit where world leaders and multiple stakeholders come together to discuss our environmental impacts and implement solutions.

And without it, the conversations would be more diluted, disjointed, and slow to progress.

The progress made year on year at COP should translate into hope for all.

The decisions we make in this decade will have long-lasting impacts and we hope the Ocean continues to receive exponentially more importance in COP28’s agenda in 2023.

In the midst of increasing climate-related disasters perpetuated by other crises, hope can be instilled through action. We need the Ocean more than it needs us. So, let’s act now – in whatever position, wherever we are. However big, however small.

![Greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain for 8 different types of food. [Credit: Our World in Data]](https://oceangeneration.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/food-type-greenhouse-gas-emissions-across-supply-chain-Generation-1024x604.png)

![Greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain for 8 types of food. [Credit: Our World in Data]](https://oceangeneration.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/food-greenhouse-gas-emissions-across-supply-chain-Generation-1024x604.png)