- Science: Explained

What is Ocean circulation – and why does it matter?

The Ocean is in constant motion.

Why does Ocean water move? Think about it. What do you need to move the Ocean? What is Ocean circulation, and why does it matter?

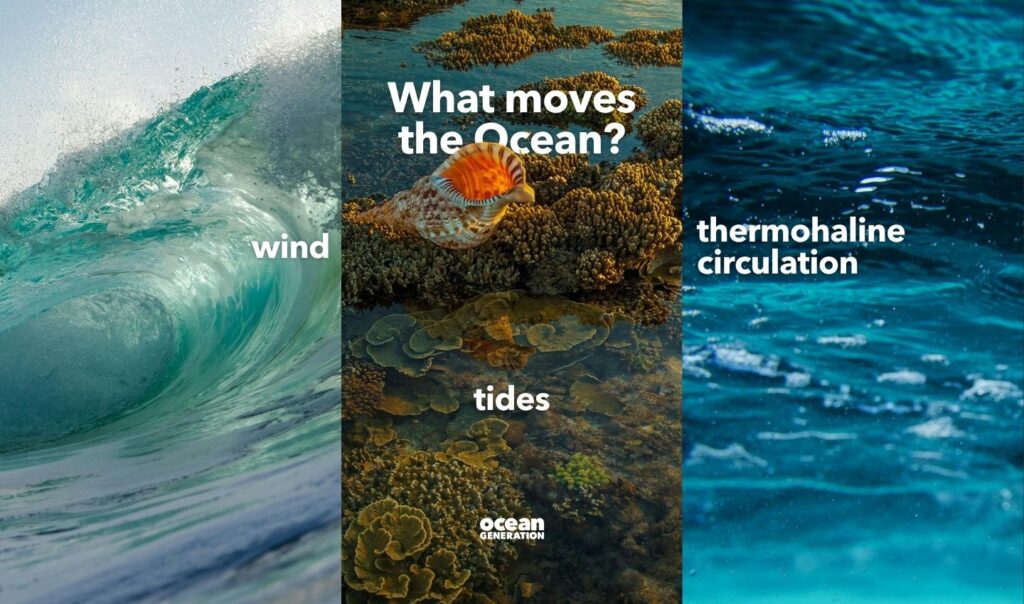

There are three drivers of Ocean currents.

The most visible driver of Ocean circulation is the wind. Big storms can whip up the waves, send them crashing into the rocks or barrelling over surfers. Waves can seem like the Ocean is moving a lot, but the water itself is moving mostly in a circular motion. We explain more in our article on the motion of the Ocean.

Prevailing winds can push the waters below in a consistent direction, such as the Gulf Stream, which does drive larger scale circulation. But usually, the wind is only moving the surface, and the Ocean is a lot deeper than the surface.

Next comes the tides. The moon, with a little help from the Sun, shifts the Ocean back and forth, changing sea level by metres in some places. The Bay of Fundy in Canada has the largest tidal range in the world, with almost 12m difference between high and low tide.

However, the tides are always changing. If tides were the only thing responsible for moving the water, then the same water would just be moved in and out. Out in the middle of the Ocean, the water would travel in a big vertical circle, like a giant Ferris wheel. To move the Ocean properly, we need something else.

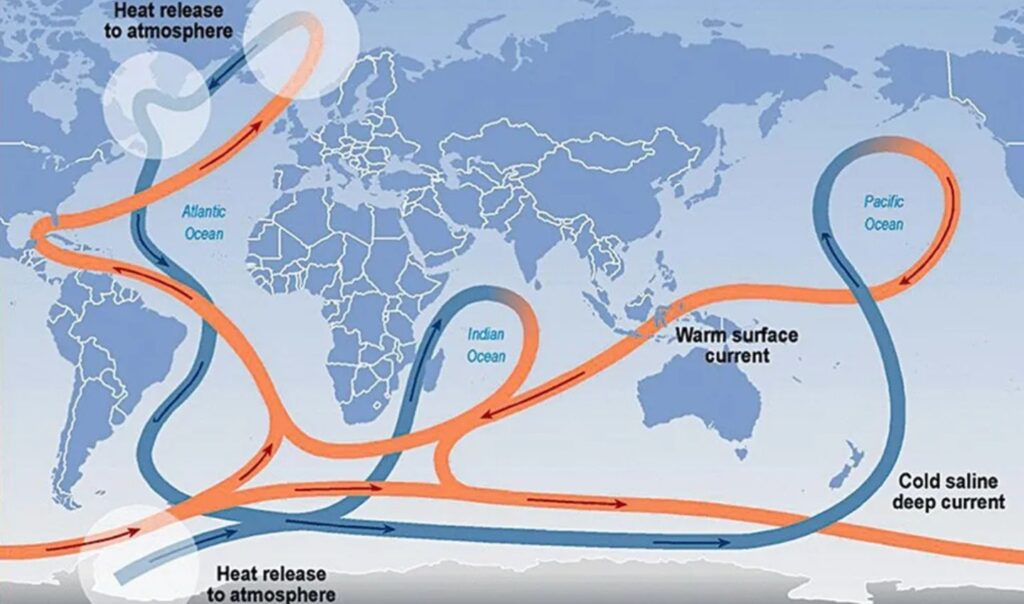

The third driver of global Oceanic currents is more understated than crashing waves or retreating seas. It takes thousands of years to move water through the deep Ocean, from pole to equator to pole. It’s known as the Ocean Conveyor, or Thermohaline Circulation, and the polar Ocean is a focal point for its activity.

Why is Ocean circulation important?

This movement of water is the heartbeat of the Ocean. It carries oxygen-rich waters to the depths, and where it returns to the surface (known as upwelling), the nutrients it brings with it create the richest waters on the planet.

The Ocean is also moving heat and carbon dioxide. It has absorbed approximately 25% of carbon dioxide emissions since the 1960s and over 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases has been assimilated into our Ocean.

The Ocean can circulate and ‘drop off’ heat and carbon dioxide in the deep. If the circulation of the Ocean slows, the surface Ocean will get hotter and more acidic. With less circulation, the Ocean’s ability to trap and store two major drivers of climate change suffers.

What is Thermohaline Circulation?

Thermohaline circulation is the slow, powerful pump behind Ocean circulation, the main driver of water movement in the Ocean. The name sounds complicated, but it tells us exactly what we are talking about.

Let’s break it down; Thermo-: we are talking about temperature; -haline about salinity, or saltiness. These two characteristics of seawater influence global climate and biological richness.

Temperature and saltiness have influence because they change how dense Ocean water is. Cold water is more dense than warm water, and salty water is more dense than freshwater. If water is denser, it will sink below less dense water.

These simple differences drive a slow, unseen conveyor belt from the poles to the equator and back again. It would take over 1,000 years for one drop of water to complete the whole Ocean circulation.

What will the cold, salty water now disappearing into the depths in the North Atlantic see when it re-surfaces in the Pacific in 3026?

Why are the Poles important for Ocean circulation?

If the poles are known for one thing, it is that they are cold. So cold in fact, they can chill seawater to the point of freezing (which happens around –1.8 to -2 degrees C / 28.76- 28.4 °F, lower than normal water due to the salt content).

When seawater freezes, it leaves its salt behind. As ice forms, the water left behind gets more salty, which lowers the temperature it will freeze at. More salt = lower freezing temperature. Very salty, very cold water is very dense, and will sink below other seawater.

This downward movement is known as downwelling. Downwelling pushes water along the depths and pulls water across the surface. This is the pump that moves the Ocean.

So begins the Ocean conveyor.

When does cold water become deadly?

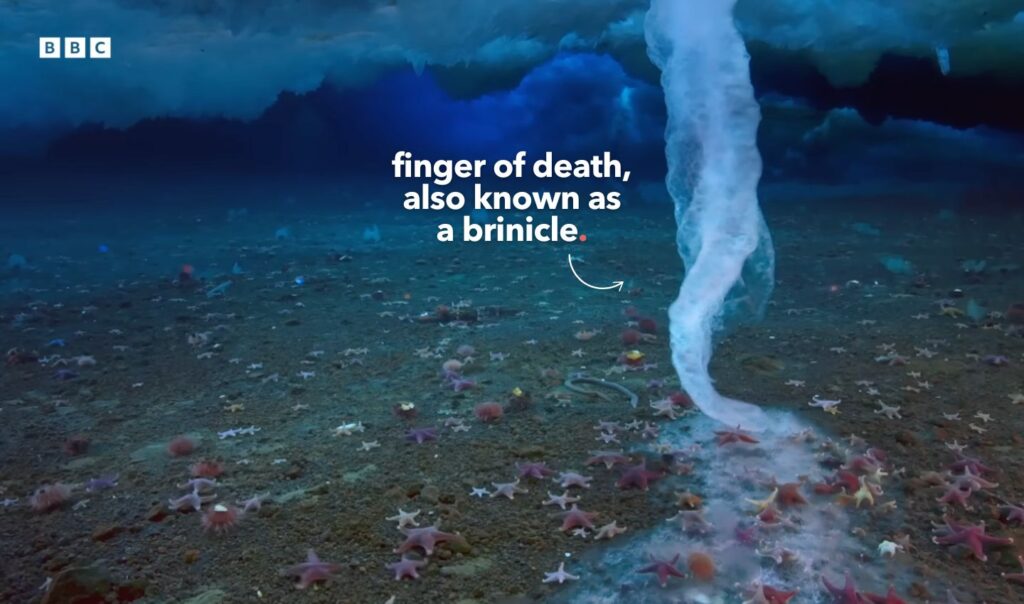

Maybe you didn’t think water movement could be exciting. Maybe you haven’t heard of the finger of death.

We know as sea ice forms, it “spits out” salt, creating channels of brine (very salty water), which is colder than freezing. This brine travels down through channels in the ice, collects more salt and cools further.

It reaches the bottom of the ice super salty and super cold. It is so cold it freezes the sea water it touches below the ice, creating beautiful brinicles.

The brine is still too salty to freeze, so travels through the centre of the brinicle, growing it. If this is in a shallow area, the brine could reach the seabed before warming and diluting enough.

This ethereal beauty then becomes a sinister threat. It is so cold it freezes anything it touches. The sea stars, brittle stars, sea cucumbers living below the ice are at the mercy of the finger of death.

Most Ocean movement isn’t as dramatic as the finger of death, but it runs on the same mechanisms.

Is Ocean circulation slowing down?

Ocean circulation relies on the cooling and sinking of water at the poles. As the release of greenhouse gases raises the temperature of our planet, especially at our poles, the water is not getting as cold.

We are seeing less sea ice form and the water has more fresh meltwater diluting it. The water is getting less cold, and less salty. Both mean the surface water is less dense, meaning it will sink less. Is the circulation of the Ocean slowing?

One way to study if it is slowing is by looking at how old the water is – older water means slower circulation.

How do you measure how old water is?

At the surface, chemicals and elements are constantly being exchanged between the air and the Ocean. Scientists can look at the chemical composition of the water, looking for indicators for when the water was last in contact with the surface.

Using Carbon-14 as a time marker

Carbon-14 is the usual way, a radioactive isotope of carbon that is used in radiocarbon dating methods from geology to archaeology. It’s also called carbon dating.

How does carbon dating work?

Carbon-14 is an isotope (type of atom) that decays slowly. Half of it will decay every 5700 years or so, known as the half-life.

Measuring the amounts of Carbon-14 can be like reading a timer. Carbon-14 is created naturally when cosmic rays hit our atmosphere, but in much larger amounts by nuclear weapons – levels doubled in the 1950s and 1960s.

This molecular ‘shadow’ has been found in marine animals in the Mariana Trench, showing just how far human impacts reach.

Track the amount of Carbon-14 and you can approximate when it was last in contact with the atmosphere, which gauges age.

Measuring human-made chemicals

Industrial chemicals such as CFC-12 and sulphur hexafluoride are other chemical clues used to age water. Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were widely used in refrigerants and spray cans until they were identified as depleting the ozone layer.

Through global cooperation and effective science, the Montreal Protocol was introduced, preventing the use of CFCs and allowing the ozone layer to recover (learn more about international treaties here). The presence of CFCs can indicate exactly when that water is from.

Using oxygen to estimate water’s age

We can also look at the Apparent Oxygen Utilisation. The principle is that deep water can’t have oxygen added, so the older the water, the more oxygen will be used up from it, meaning older water has less oxygen.

Despite fluctuations caused by other Ocean movers (e.g. the wind), the waters in the deep North Atlantic are getting older, implying the water is not being replenished as quickly, and therefore that the circulation is slowing. The same is happening at the other pole.

The Ocean is made up of many different ‘bodies’ of water, with different characteristics and names. North Atlantic Deep Water is formed in the Arctic by cold, salty water sinking and flowing south. This water travels all the way to the Southern Ocean, where it meets another body of water.

Antarctic Bottom Water is formed at the South Pole and is the coldest and the densest of them all, the real powerhouse of Ocean circulation. But it is warming and there is less of it. The frost-fuelled engine is slowing.

What would a broken Ocean conveyor mean?

The Ocean would suffer.

Deep sea creatures relying on delivery of oxygen and nutrients would be left waiting, as deoxygenated areas grow. The same would happen for surface species that need the upwelling of nutrients from the deep.

If Ocean circulation stopped, there would be dead zones without oxygen in the deep and starved surfaces with no nutrients to support phytoplankton.

It would impact life on land too. If the circulation of the Ocean slows, global climates will shift. Increased storm intensity, more extreme weather patterns and changes to rainfall. Europe could face far cooler temperatures as the tropical water that brings warmth from the equator slows.

That is quite a big if, and fortunately, the Ocean is resilient. New work has shown circulation has slowed in the 2010s and 2020s by less than in the 2000s. This has been attributed to natural variability pushing against the human-caused weakening.

Every reduction in greenhouse gases, every degree of warming prevented, reduces the stress on our Poles and on our Ocean circulation. Keeping our poles cool keeps our Ocean moving.