- Science: Explained

Marine discoveries and Ocean wins in 2025

What were the Ocean wins in 2025?

The past year has seen some amazing developments in our understanding of and our relationship with the Ocean. We’re unpacking: what Ocean discoveries have we made, what Ocean protection have we brought in and what Ocean recovery have we seen in 2025?

Jump to:

- What Ocean discoveries happened in 2025?

- What Ocean protection happened in 2025?

- What Ocean recovery have we seen in 2025?

What Ocean discoveries happened in 2025?

New clownfish related discoveries

Over the course of 2025, there have been a series of discoveries centred around the clownfish, made famous by Nemo and Marlin in Finding Nemo (see our scientific analysis of the film here).

How does the clownfish avoid being stung by the anemone?

By having lower levels of sialic acid on their skin, clownfish avoid being stung by anemones. Sialic acid can be found on the outer surface of most animals – it is important in cell-to cell communication and immune response. The nematocysts (stinging cells) of the anemone have a special trigger, to avoid the anemone constantly stinging itself. Researchers found the fish that can live in an anemone have low levels of sialic acid, to ‘hide’ from the anemone, and avoid triggering its stings.

We discovered that the relationship between clownfish and anemone isn’t as one-sided as it may seem.

Anemonefish have been observed feeding their anemones large food they can’t eat, or extra food after they have eaten their fill. This has also been shown to increase how fast anemones grow.

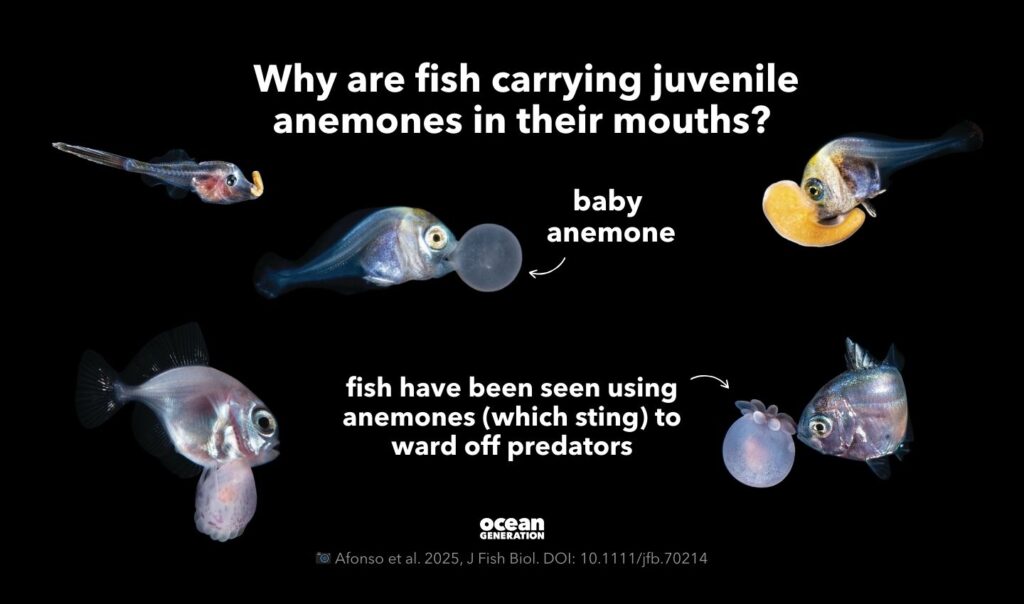

Why do fish carry anemones around in their mouths?

Clownfish aren’t the only ones buddying up with anemones. Several species of fish have been photographed holding larval (baby/ juvenile) anemones in their mouths.

The assumption is that they are effectively arming themselves with marine (live) pepper spray. Predators can be warded off with a nasty sting. The anemones also benefit, as the young fish can swim and be swept much further than the anemone would normally reach.

The young fish have a predator deterrent, and the anemone gets a lift to a new neighbourhood.

What new Ocean species were discovered in 2025?

A new species of manta ray was distinguished in 2025, adding a third species to the manta ray family.

Until 2009, there was only one species of manta ray. In a study focussed on morphological characterisation, analysis of colour, teeth and other traits differentiated the reef and Oceanic manta rays.

In 2025, after years of speculation, it was confirmed that there was a third species of manta.

Lead author of the study identifying the Oceanic and reef manta species, Dr. Andrea Marshall, had theorised a third species after diving in the Atlantic Ocean with manta rays she didn’t recognise. Years of study, including the description of a type specimen and genetic analysis, have confirmed her hypothesis: a third species of manta ray exists.

Facts about the newly discovered manta ray:

Mobula yarae, more commonly known as the Atlantic manta ray, are named after Yara, the ‘mother of waters’ from Indigenous Brazilian mythology.

Telling them apart from other manta rays starts with size: they reach an approximate size of 6m across, sitting between the Oceanic and reef manta in size. A ‘V’ shaped white shoulder patch, lighter colouration around the mouth and eyes and dark spots confined to the belly rather than between gill slits are the key identifying features.

The Ocean Census announced that it has facilitated the discovery of 909 new Ocean species.

The program, in its second year of running, hopes to fast-track Ocean discovery, and so far has increased the annual speed of species discovery by 38%.

A new kind of shark discovered

Sticking with our elasmobranchs (cartilaginous fish that include sharks, skates, and rays), a new kind of guitar shark was discovered off the coasts of Mozambique and Tanzania. It joins 37 other guitar sharks in one of the most threatened vertebrate families, with two thirds of them threatened.

New species of snailfish in the deep-sea

Looking deeper in the Ocean, a new species of snailfish was discovered 3,263m deep.

The suitably named ‘bumpy snailfish’ is only two to three inches long and was one of three new snailfish species found on the expedition led by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

There are over 400 species of snailfish, and the family holds the record for the deepest dwelling fish, with one found 8,338m deep.

Meet a newly discovered sea sponge: the Death-ball sponge

As one of the more notably named, the death-ball sponge (Chondrocladia sp. nov.) received a lot of press.

Where most sponges unobtrusively filter the water for food (ensuring highly efficient nutrient circulation where there isn’t much to go round), this new species has a number of ‘balls’ covered in tiny hooks to trap their prey.

New deep-sea discoveries with celebrity nicknames

There were a couple of famous characters whose semblances were discovered in the deep Ocean.

- A deep-sea coral first spotted in 2006, but formally described this year, was given the name Iridogorgia chewbacca, due to its long hairy branches.

- An iridescent scale worm found in the freezing waters of Antarctica was given the nickname ‘Elvis-worm’, its sparkling scales shimmering in the deep like the sequins of the King of Rock and Rolls’ jackets in Las Vegas

- And a bonus one (not a new species): the colossal squid was caught on camera in its natural habitat for the very first time. This one wasn’t all that colossal: it was a juvenile just 30cm long.

What Ocean protection happened in 2025?

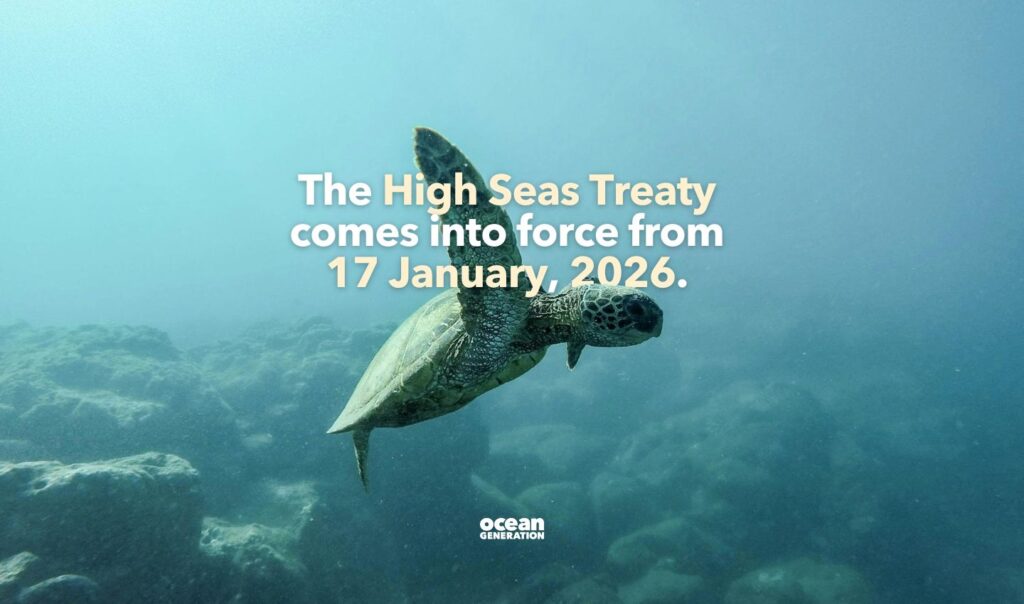

60 countries ratified The High Seas Treaty in 2025

In September, the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction reached 60 ratifications, the milestone required to start the countdown to it becoming legally binding. From 17January 2026 the agreement, also known as the biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ) or High Seas Treaty, will enter force.

Read more about the High Seas Treaty here.

Many countries have been protecting the Ocean off their coastlines in 2025.

Countries haven’t been hanging about, waiting for the High Seas Treaty, they have been getting on with Ocean protection in their own patches.

Marine Protected Area, or MPA, is a general term for an area of Ocean in which human activities are managed or limited to protect the marine world. Depending on what they are aiming to protect, they can have different rules. Some will allow sustainable fishing and recreation; others may be no-take zones where no fishing is allowed.

What is the largest marine protected area in the world?

French Polynesia announced the creation of the world’s largest marine protected area in 2025. The protection of their entire exclusive economic zone, an area of 4.8 million square kilometres, now includes 1.1 million square kilometres of highly protected waters.

An exclusive economic zone is the area of Ocean extending up to 200 miles from the coast of each country, in which they have the rights to explore and utilise any marine resources.

A huge no-fishing zone has been expanded in the South Atlantic Ocean:

For Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) around South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (not where sandwiches were invented), the ‘no take zones’ where no fishing can occur have been expanded to over 470,000km2, 38% of the MPA. This is to help protect the migration routes of humpback whales.

How whales are being protected in marine sanctuaries:

That isn’t the only help we’ve given our whale friends. In October, a proposal for a huge marine sanctuary in the North Atlantic was approved. Macaronesia is an area including the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands and the Cabo Verde islands. It’s rich in marine biodiversity, hosting 32 different species of cetacean. (Cetaceans include whales, dolphins and porpoises.)

The new marine sanctuary will hope to protect the Ocean from increasing pressures of boat traffic, underwater noise, industrial fishing and future threats such as deep-sea mining.

Do marine protected areas really help protect the Ocean?

In a little win of its own, a research paper was published this year that showed that fully and highly protected marine areas do work.

There have been concerns that enforcement around MPAs isn’t feasible, any fishing vessels can just ‘go dark’ – turn off their identification systems and continue poaching.

But analysis using artificial intelligence and satellite imagery has shown very little industrial fishing activity in highly protected MPAs. Conversely, there was substantial activity in MPAs with low protection.

We’re protecting more of the Ocean, and it is working.

What is the EU Ocean Pact?

On money, the European Commission launched a unified framework for EU Ocean policy in 2025, backed by a €1 billion investment in the Ocean, with six priority areas including: habitat restoration, decarbonisation of maritime sectors, blue economy competitiveness, coastal/island community support, Ocean diplomacy and innovation.

Progress on cutting shipping emissions

Member States of the International Maritime Organisation agreed a global standard for decarbonising shipping: fuel‑intensity reductions, global emissions pricing for ships, and a fund for low/zero‑emission marine fuels.

The agreement was agreed but not formally signed, as in a meeting in October 2025 delegations from Saudi Arabia and the United States lobbied for a delay.

This is half a win this year and will hopefully be a full win for our Ocean in 2026, in a sector that accounts for around 11% of global emissions in transport.

What Ocean recovery have we seen in 2025?

Are whale populations bouncing back?

In a paper published towards the end of 2024 that examined historic databases on whales, it was suggested that we underestimate the longevity of whales by some distance.

How old do whales get?

Our estimates for the average age of whales were first shaken in 1979, when Japanese whalers found individual blue and fin whales that were 110 and 114 years old respectively. Prior to this, we understood these animals to live to 70 years.

This 2024 paper attributed the lower perceived longevity to our success in whaling. Whales weren’t living as long because we were hunting them.

But the world is changing. Whaling was made illegal in 1987, and populations have shown promising signs of recovery. Over the course of 2025 there were several markers of a better world for whales, and hints of the future we are creating for them.

The Atlantic Northern Right Whale, one of the most endangered whales, has enjoyed an increase in population, up 8 individuals to 384 whales. This is off the back of a decade in which the population declined by 25% between 2010 and 2020 due to ship strikes and entanglement.

2025 saw the cancellation of the Icelandic fin whale season, meaning once again no fin whales were killed due to an unfavourable market, marked by diminishing demand for whale products and rising costs.

Who is ‘crush’ing it? Green turtles are no longer endangered.

It’s a good time to be a green turtle (Chelonia mydas). The species, made famous by Crush and Squirt in Finding Nemo, has been upgraded on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, from Endangered to Least Concern.

To best help them, we had to understand what was hurting them. Green turtles (and other sea turtle species) have long been hunted for their meat and their eggs, so legally protecting them was a good first step.

When did we start protecting sea turtles?

Legal protections started coming in in the second half of the 20th century, with bans such as that on Aldabra Atoll in 1968 safeguarding turtle mothers and their eggs. Since that ban, green turtle egg clutches have increased 410−665%.

Even without the pressures of hunting, turtles still faced a struggle, becoming the poster of plastic pollution and entanglement in fishing gear, and facing the realities of a changing Ocean.

But conservation efforts have continued. Excluder devices (devices designed to prevent bycatch) have been implemented on fishing gear to avoid entanglement. Nesting beaches have been protected from light pollution that could lead hatchlings away from the Ocean, or plastic pollution that could tangle or choke them. Turtle hatchlings have been released at sea to give the population a boost.

Green turtle numbers are now up 28% compared to the 1970s.

Some sub-populations are still struggling and need help, but it shows us, again, that the Ocean has a great capacity to recover when we allow it.

“The ongoing global recovery of the green turtle is a powerful example of what coordinated global conservation over decades can achieve to stabilise and even restore populations of long-lived marine species,” – Roderic Mast, co-chair of IUCN’s Species Survival Commission Marine Turtle Specialist Group.

Dam Good News for salmon

In 1878, a lamp turned on. In itself, not a remarkable event, but this lamp was special. It was powered by water.

Cragside House in Northumberland, England, saw the birth of hydroelectric power. Within ten years, hundreds of hydropower stations were running around the world. It remains the third largest source of electricity globally, behind coal and gas. Until 2004, it represented over 90% of the world’s electricity generated by renewables and is still over 50%.*

Benefits of hydropower

Our World in Data compiles the data to examine its benefits. Hydropower is incredibly safe, with the 1.3 deaths per terawatt hour of electricity produced far lower than coal’s 24.6, and almost all from a single event: the Banqiao Dam Failure in China in 1975, which killed 171,000.

Hydropower is very clean, producing an average of 24 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per gigawatt hour, compared to coal which produces 970 tonnes. A world without hydropower would likely be a world that had burned more fossil fuels.

Disadvantages of hydropower

However, hydropower isn’t all turbines and waterfalls – it comes with its limitations. It’s expensive, especially in upfront cost. It also has an environmental impact beyond carbon emissions.

Huge dams create reservoirs, flooding land and cutting off rivers. Cutting off the rivers can lead to drought or famine downstream. Reservoirs can emit greenhouse gases by creating large areas of stagnant water full of decomposing material. As solar and wind have become far cheaper and more accessible, there is less need for the large projects.

Salmon, returning home after 100 years:

In 2023, the world’s biggest dam removal project re-opened the Klamath river in California and Oregon.

The project was initiated by local populations after 30-70,000 salmon died below the dams in 2002 due to low flow, the costs of maintenance and repair coupled with environmental costs and the reservoir’s proclivity to harmful algal blooms.

This year, the salmon returned to the Chiloquin Basin for the first time in over 100 years.

“A hundred and fifteen years that they haven’t been here, and they still have that GPS unit inside of them. It’s truly an awesome feat if you think about the gauntlet they had to go through.” said the visibly giddy Klamath Tribal Chair William Ray, Jr.

This is a story mirrored elsewhere in the world too – salmon returned to the river Don in England for the first time in two centuries this year.

As we explored in some articles earlier in 2025, rivers and residents like salmon are vital in connecting different ecosystems.

Hydropower can prevent the salmon migrating and breeding in their ancestral waters and poison the rivers they grow up in. Losing that connection impacts the people and life all along the river.

We need energy to reinforce our high quality of life. That used to come at the cost of our natural environment. However, we are more aware of that impact, and we are getting far better at diminishing it. Stories like this are sprinkled with glimpses of a bright future, in which humans can flourish with nature.

This pattern – discovery igniting protection, protection enabling recovery – reflects how our relationship with nature has evolved over decades, not just this year.

The Ocean wins of 2025 demonstrate a shift in our relationship: we are learning to value and safeguard our seas, and in return, the Ocean is proving its remarkable capacity to heal.

In ten years, we hope stories of recovery and flourishing will dominate the narrative, as the need for more protection fades.

Discovery is good too; it will always be fun to hear about new death-ball sponges and bumpy snailfish.

* Energy Institute – Statistical Review of World Energy (2025)