- Marine Life Facts

- Science: Explained

Narwhals and Unicorns: How the magic of the Arctic has changed

Are unicorns real? Look to the Arctic Ocean.

Under a clear blue sky, icebergs silently sparkle as they float in the Ocean, occasionally nudging each other. The water between them is a deep blue and still, undisturbed. Until a twisted ivory lance pierces the air, sliding out of the water inch by inch until two metres of tusk are followed by a mottled grey head. The head directs the tusk down again, exhales through the nostrils on top and takes a deep breath, slipping into the frigid waters.

Maybe not quite how you would picture seeing your first unicorn.

Except there’s some bad news. Unicorns aren’t real. We are as disappointed as you are; the closest we can come to a unicorn is a whale that lives in the Ocean: narwhals.

But there was a time not so long ago that people believed the unicorn existed.

Why did people believe unicorns existed?

In the first half of fourth century BC the Greek physician Ctesias provided the first description of a unicorn. He outlined an Indian wild ass (a horse-like animal) with a crimson head and a tri-coloured horn about 28 inches long. He wrote that powdered unicorn horn acted as an antidote to deadly poisons.

Aelian, a Roman writer in 200 AD fleshed out the description and noted that only noblemen could afford the horns, they were so expensive.

Early Christianity adopted the unicorn as a symbol of Christ, with the horn as a symbol of the cross of Christ. Through the belief in protection for the self and the soul, the unicorn horn – known as alicorn – became a highly sought after asset.

Unicorn horns were symbols of wealth and power, often displayed in positions of prominence on banquet tables. It was thought that the horn would bubble if dipped in a poisoned chalice, saving the wielder – a popular tool in the medieval banquet hall.

At the peak of its popularity, a complete horn was worth 20 times its weight in gold*, and even powdered horn once cost ten times.

Unicorn horns were sought after by nobles, kings and religious leaders in Europe:

For example, Lorenzo de Medici had one valued at 6,000 gold florins (around $1 million). Ivan the Terrible was reported to have paid 10,000 marks for one, and called for it to be brought to him on his deathbed. Martin Luther was said to have been saved from an assassination attempt by powdered unicorn horn, and had a spoon made from the magical substance.

Such a powerful tool befits a queen, and on hearing that Mary Queen of Scots was using unicorn horn to test her food for poison, Elizabeth I offered a handsome reward for another. Privateer and Arctic explorer Martin Frobisher (or Humphrey Gilbert, both were on the expedition, but different sources credit them) found a narwhal washed ashore in Canada and gifted it to the queen. She was enamoured with it and covered it in jewels. It was said to be valued at £10,000*, approximately £3 million in modern terms. She also handed a gilted and bejewelled unicorn horn drinking vessel down to James I.

Even the Pope, one of the main focal points of power and wealth at the time, was involved. Pope Clement VII gifted Francis I of France a unicorn horn on a silver stand.

In the 1660s, King Frederick III ordered the building of a coronation chair. This chair was made using several unicorn horns and served as the centrepiece of Danish coronations until 1840.

But as we know, unicorns aren’t real. Where are these horns coming from?

Where did tales of unicorn horns come from?

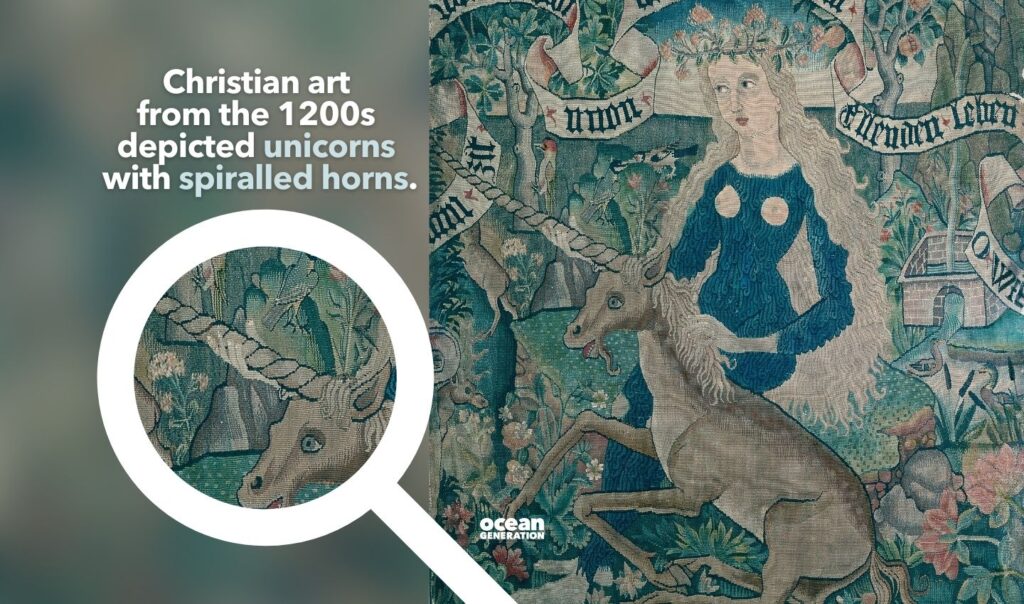

Most of the Roman and Greek accounts of unicorns were likely based on stories from travellers coming across rhinoceros in India and Africa. But after these initial accounts describing the horn as straight, Christian art from about 1200 changed its view of the unicorn.

Unicorns now had spiralled horns. There is only one animal that possesses a straight, spiralling ‘horn’ – the narwhal (Monodon monceros). And it isn’t a horn at all, but a tooth.

What you need to know about narwhals: unicorns of the sea

The name comes from the Old Norse nárhval, meaning corpse whale. Narwhals have mottled grey skin not dissimilar to rotting flesh and like to lounge at the surface – behaviour known as logging. Combine the two and you can understand why the Viking explorers named them.

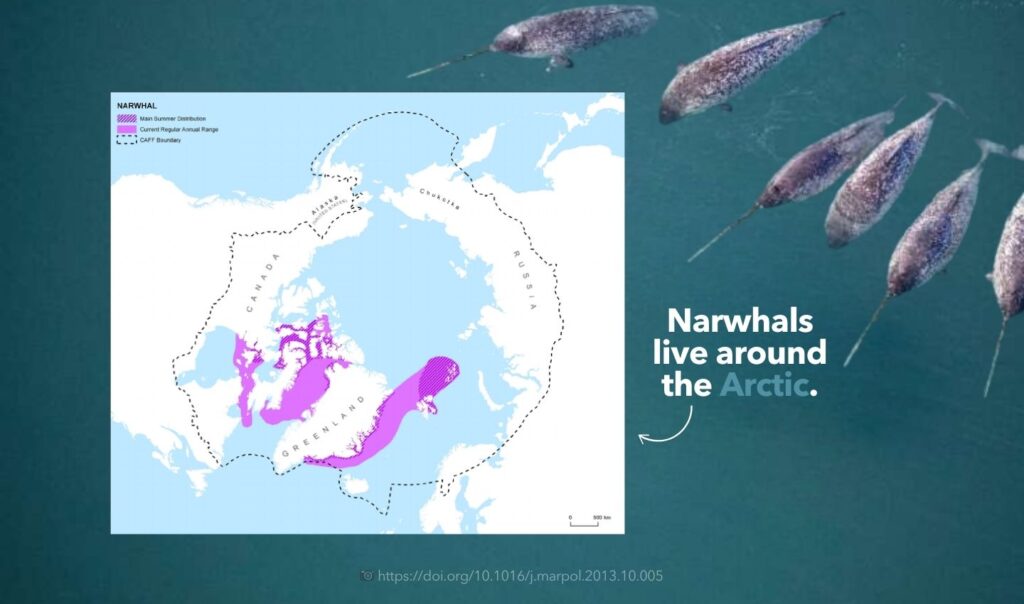

Narwhals are homebodies. They have ‘high site fidelity’ – meaning they stick to the places they like and will go back to their favourite spots. They can be found in the Canadian Arctic, through to East Greenland, Svalbard and the western Russian Arctic.

What is a narwhal’s ‘horn’?

The ‘horn’ of a narwhal is one (or in rare cases two) of the incisors, so is a tusk rather than a horn at all. All narwhals have two tusks embedded in their top lip.

Most commonly, males in their 2nd or 3rd year will have the front left tusk erupt through their top lip, growing with age to reach 1.5-2.5m long. Around 3% of narwhals are anomalies, with some females growing tusks, some males growing two or none at all. Double tusks in narwhals are about as common as an extra finger in humans.

What do narwhals use their tusk for?

The use of the tusk is still under debate.

The first theories were that narwhal tusks were used for piercing prey or breaking up ice to make breathing holes. Observers supposed they could also function as a defensive mechanism or a cooling system. However, these theories are either discredited or unproven. The real uses are even more spectacular.

Dental Displays

Studies suggest that narwhal tusks are sexually selected. Male narwhals will use their tusk as a display feature in competition with each other, and bigger is better. The size of the tusk has been shown to positively correlate with teste size – so could be an easy indicator for the females to see which males are most fertile. Sometimes, size does matter.

Where males with similar tusks meet, they may fight – male narwhals show far more scarring on their heads than juvenile and female narwhals and 40-60% have broken tusks, but this hasn’t ever been observed.

What is sexual selection?

Sexual selection is a special type of natural selection, where traits that increase reproduction will be passed on.

Fish Fencers

But it isn’t just for showing or skirmishing. Using drones to study the narwhals’ behaviour, researchers saw the tusks in action. They could use the tusk to guide the fish, chasing it. They even saw the tusk being used, as a thresher shark uses its tail, to hit the fish, stunning it ready for eating. The scientists involved think there could even have been an element of play.

Temperature Taster

In 2014, we discovered that a narwhal tusk was full of holes and nerves. This could mean that it can operate as a water sensing tool for the narwhal, and they can ‘feel’ changes in water saltiness (salinity) and temperature. They show elevated heart rate when the horn is exposed to very salty water and fresh water, suggesting they can detect it.

‘Feeling’ your surroundings can be very useful for navigation, when diving deep and moving between their favourite spots. It could also save their lives. Seawater freezing depends on the temperature and salinity of the water – saltier water needs to be colder before it freezes. By knowing the temperature and salinity of the water they are in, they are detecting when the water is likely to freeze, trapping them from the air to breathe.

This could also be used in hunting – those narwhals we’ve seen using their tusks to ‘chase’ fish? They could be using their swirly sensor to detect the fishes’ movements through pressure changes in the water, even faster than they can see them

Are narwhals magic?

So, we have a tooth that helps guide them through the icy waters like Rudolph’s nose, zero in on prey like a laser guided missile and show off their suitability to be a parent.

A narwhal’s tusk could enable them to tell when ice is going to form and find prey hiding in the dark as they can dive over a kilometre (3,281 ft) down, where no light can reach.

Unicorns might not be real, but this all sounds like magic.

Does something lose its magic just because we understand how it works? Whether it is magic or incredible biology, the enchantment of the narwhal is threatened by a changing world.

How is the narwhals’ world changing?

The opinions and doting of nobles across Europe and the world meant nothing to the narwhal. After years of hunting operations, narwhals are now enduring other changes, this time in their home. Climate change, caused primarily by the human burning of fossil fuels, is hitting the polar regions, where narwhals live, the hardest.

The Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the world. This is known as polar or Arctic amplification (AA). AA has resulted in the Arctic warming by as much as four times the rest of the globe. Since 2006, the air temperature in autumn and winter has increased by more than twice the global average.

Why do narwhals live in the Arctic Ocean?

Narwhals like it cold. Where the sea is warmer, there are less narwhals. Why? This could be to do with their prey – one of their favourites, cod, are known to grow better in water temperatures of less than 2 degrees.

It could also be to do with their supreme adaptions for the coldest places on the planet – they may overheat at higher temperatures. No one wants to be wearing a thick winter coat on a hot summer’s day.

How is climate change impacting narwhals?

There is less ice. November 30 2025 saw the lowest area of Arctic ice on that date on record. The previous 20 years have given us the 20th lowest sea ice minimums on record, and there is 95% less old sea ice (over 4 years old) than the average from 1979-2004.

Ice is an important part of the lives of every animal living in the polar seas. The loss of sea ice has been shown to change the diet of the narwhal as they can’t eat ice-based (known as sympagic) prey, so they eat more open-water (pelagic) species instead.

Through burning coal and mining for gold, humans have increased the amount of mercury in the environment. Less ice means there is more bioavailable mercury. The result: the narwhals are exposed to more mercury. Increased mercury levels can impact the reproduction and immune systems of narwhals. How do we know this? Through analysing narwhal tusks, which give us an insight into their life history. The magic tusks are whispering to us.

The reducing ice also means there is more human activity. We are a noisy bunch, and narwhals have shown to be sensitive to ship noise, reducing their deep dives for food (and given they are inefficient in their dive success, they need them).

How are we preserving the magic of the Arctic?

Narwhal hunting is monitored and almost every whale caught is for the subsidence of the indigenous Inuit people. The population is difficult to track, especially without a reliable baseline. However, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature assessed the population in 2017 and shifted the status from Near Threatened to Least Concern. The narwhal is doing well so far.

The isolation of the Arctic and the changing attitude towards cetaceans means the narwhal hasn’t had to deal with a multitude of human pressures. But more than ever, those pressures are finding them where they log.

Research will continue to develop quieter boats, and policy will increase protected areas. The narwhal is one example of a bit of remote magic we are trying to keep.

Climate change is being tackled head on, with an energy transition in full flow, electric vehicles going from strength to strength and global emission increases are slowing. We will be the generation to see the transition to human flourishing not coming at the cost of our natural world, for the first time.

But within this, driving this, is being able to see the magic of the unicorn, not as a made-up money-making monopoly manufacture, but in the reality of the narwhal and its beautiful, magical tooth. See the magic, spread the magic – that is what will lead to us protecting the magic.

*Wexler, P. (2017). Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Academic Press.

Cover image by Проектный офис Нарвал