- Science: Explained

Why krill matter: Krill fishing and conservation in the Southern Ocean

The Southern Ocean is one of the most remote places on the planet.

It was only in 1911 that the first human, Roald Amundsen, reached the South Pole. For context, the first powered aircraft, the Wright Flyer, took to the air in 1903. Humanity conquered the skies before it managed the southern continent. The waters here are cold, barely above freezing, yet full of life. These are some of the richest waters in the world.

The main character is just 6cm long. Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) are small, shrimp-like crustaceans. They snack on the phytoplankton that thrives in the long hours of summer sunlight, trapping and storing similar amounts of carbon to seagrass and mangroves.

Their importance lies in their numbers: krill swarms are vast. The rust-coloured clouds are filled with billions of individuals and can be visible from space. They sustain most of the life around Antarctica. Penguins, seals, whales, fish and sharks all rely on this buffet: krill are a keystone species. More recently, people have joined the party.

Krill fishing has become a divisive topic, being featured in David Attenborough’s Ocean, calls to ban it being promoted at the United Nations Ocean Conference and some retailers withdrawing krill products from their shelves. Meanwhile, countries have applied to increase the catch limits and the amounts of krill being fished are higher than ever.

To understand where we are going, first we can look at where we have been. Why are krill important? What is our history in the Southern Ocean? What is our future?

How did we get here?

In 1775, Captain James Cook returned to England from a voyage around the world, in which he had searched for new lands. He found there wasn’t a new continent in the Pacific Ocean (at least not where one was predicted to be) and hypothesised on the existence of Antarctic land behind the ice (which he was correct about).

He had discovered some land on his travels: an island populated by seals and penguins, which was named ‘Isle of Georgia’ in honour of King George III of England. We know it now as South Georgia.

Sealing and whaling in the Southern Ocean

The element of Cook’s report that got attention was the abundance of fur seals on South Georgia and neighbouring islands. These pinnipeds were highly sought after, and between 1778 and 1822 an estimated 1.2 million fur seals were killed for their pelts. The species was almost completely wiped out on South Georgia and the islands.

The rise of industrial whaling then turned focus on to the waters of the Southern Ocean around South Georgia. Factory ships and explosive harpoons reduced the great whales to 18% of their original population. 5% of blue whales were left, and just 3% of humpback whales survived. When the last two whaling stations closed on South Georgia in 1965, 175,250 whales had been killed in those waters.

When did krill fishing start?

Industrial fishing had been largely unmanaged, and everyone raced to benefit from the natural resources the Southern Ocean had to offer. One by one the marine species of the south had been targeted to great effect, and populations crashed. The focus then shifted to krill.

Industrial fishing for krill in the Southern Ocean increased through the 1960s and 1970s. As the species that formed the foundation of the ecosystem, the alarm bells rang, loud, at the prospect of the krill suffering the same fate as the seals and the whales.

Why are krill important?

Krill are a keystone species

The loss of krill would be disastrous for many different species. Whales, seals, penguins and fish are all krill predators. Less krill means less food for these species.

Southern Right whale mothers have shown a decrease in body condition over the past 40 years, suggesting ecological strain on an animal heavily reliant on Antarctic krill.

The population of krill has been linked with Adelie and chinstrap penguin numbers – when there is less krill, the penguin populations decrease. And the fur seals, populations freshly rebounded from the hunting of the nineteenth century, are showing declines due to krill availability.

Without krill, life in the Southern Ocean could collapse.

To relay it in economic terms, krill are a vital piece of an ecosystem that provides, conservatively, $180 billion annually in ecosystem services – about 70% of New Zealands GDP in 2024.

Krill are climate champions

It isn’t just the animals in the Southern Ocean that depend on these. Krill are big players in the balancing of our atmosphere. They trap (sequester) a lot of carbon.

As phytoplankton photosynthesise, they take in carbon dioxide. When they are eaten by krill, the krill take on that carbon, some of which is then… dropped off. Krill faecal pellets (poo) alone are estimated to sequester 20 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year. Depending on the price of carbon, this is worth between $4 and $46 billion.

Marshes, mangroves and sea grass are estimated to absorb 13, 24 and 44 million tonnes per year respectively, so when you add in the extras of krill moults (20 million tonnes) and migration (26 million tonnes), as the researchers say: “it is likely that Antarctic krill is amongst the world’s most important carbon-storing organisms.”

How is krill fishing managed in the Southern Ocean?

Those alarm bells over the fishing of krill led to the creation of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR). It was formed in 1980 and entered force in 1982.

The CCAMLR is made up of 27 member states (as of January 2026), with a further 10 ‘Acceding’ states – that support but don’t contribute to the budget or take part in decision making.

The stated aim: to protect and conserve the ecosystem of the Southern Ocean. Article II of the convention states:

- The objective of this Convention is the conservation of Antarctic marine living resources.

- For the purposes of this Convention, the term ‘conservation’ includes rational use.

This captures a crucial distinction: fishing is an element of conservation, rather than an adversary.

How do you prevent overfishing?

Catch Limits

A general rule of thumb is that you can’t remove so much the population can’t sustain itself. That will vary with species – some animals reproduce a lot faster than others.

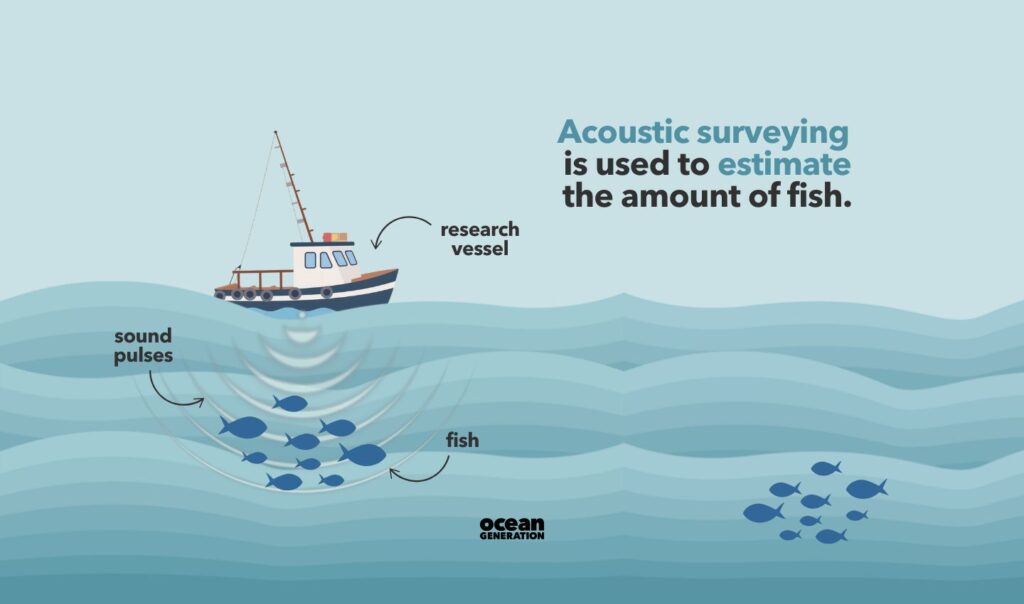

Understanding how much of a resource there is, is fundamental to managing it. This is one of the biggest obstacles in the Ocean: the water means you can’t just see (sea). In a field you can see how many cows there are, not true of a shoal of fish.

Acoustic surveying (using noise to find out what is there, like a bat) gives us estimates for the amount of krill. In short – a lot. We estimate there are over 300 million tonnes of Antarctic krill, roughly the same as the biomass of humans.

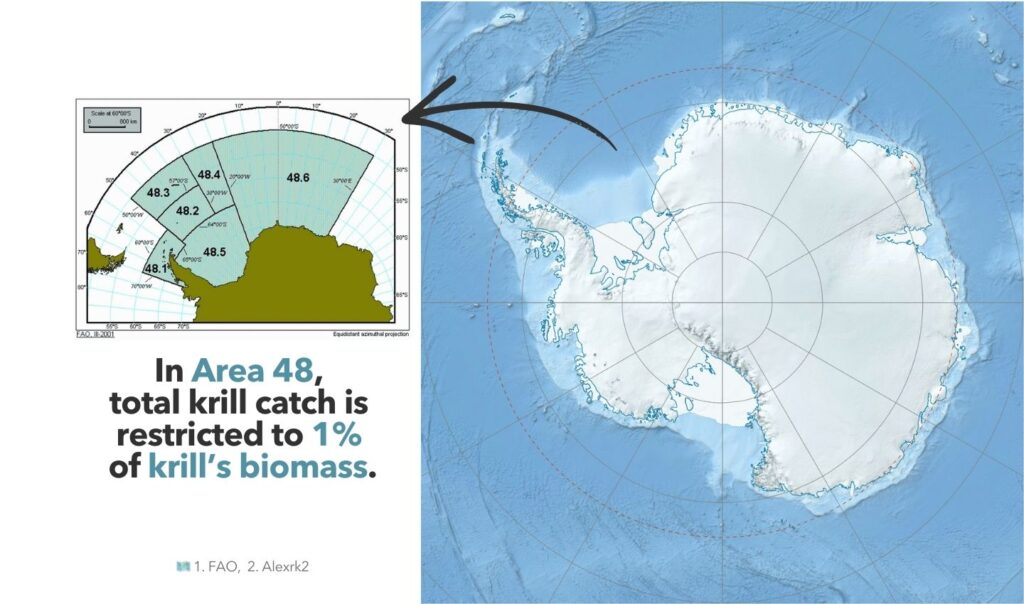

In the specific area targeted for krill fishing (known as Area 48), the biomass is estimated at 62 million tonnes (coincidentally, roughly the same mass as annual e-waste produced). So, CCAMLR adopted Conservation Measure 51-01. CM 51-01 set a trigger level at 1% of that biomass (620,000 tonnes) – when that is reached, all krill fishing stops, no questions asked. August 2025 was the first time this happened.

Marine Protected Areas

Another tool in the toolbox is protected areas – designated places with specific rules. Choosing to avoid fishing in nursery areas, or places with high densities of predators, can ensure the health of the fishery.

The Southern Ocean is home to the first MPA on the high-seas (outside of the jurisdiction of any one country) and the largest. The South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf MPA was created in 2009, and is a no-take zone protecting penguin foraging areas.

The Ross Sea MPA was created in 2016 and is 2.09 million square kilometres, 72% of which is a no-take zone. The MPA has a controversial “sunset clause”, meaning the MPA will expire in 35 years unless renegotiated.

There are four other MPAs that have been proposed, but not yet agreed on.

Has the management of krill worked?

The krill fishery is one of the most closely managed in the world. Every single ship has an independent scientific observer on board to ensure catch and bycatch amounts are accurately reported. There is zero illegal, unreported or unregulated (known as IUU) fishing putting additional pressure on stocks.

Bycatch rates are very low. In 2004, after pressure to report bycatch, it was revealed 292 fur seals had been killed as bycatch. This prompted the fishery to adopt mitigation measures, and since 2010, 39 fur seals have been killed. This is alongside 7 humpback whales and 80 seabirds.

In many senses, this is a great success. Krill populations are stable and there have been little ecological impact from fishing. No other large-scale fishery in the world is as well-monitored, as efficient (in avoiding by catch) or conservative with catch limits. The industry refers to these points as support for increasing the limits.

It’s not just ‘how much’: Why location-specific catch limits matter

The numbers look excellent. However, the risk lies in local depletion. Taking 1% isn’t much unless you take it all from one place.

Penguins, seals and whales need the krill within reach. They can travel to find them, but the further they go, the more energy they spend to get there and the less far the meal will go.

To make an analogy:

It is like buying sweets. If you have £10 to spend on sweets, you could either buy lots of different types of sweets or spend all the money just on fudge. If you do the latter, Timmy from down the road might not get the fudge he wants because you bought it all.

To avoid krill fisheries removing the entire quota from one area and leave the local penguins hungry, CCAMLR introduced Conservation Measure 51-07 (CM 51-07). CM 51-07 divided the catch limits in area 48 into Subarea 48.1 (25%, 155,000t), 48.2 (45%, 279,000t), 48.3 (45%, 279,000t) and 48.4 (15%, 93,000t). It added another layer of protection to CM 51-01, but was a temporary measure with an expiry date, to incentivise agreement on long term measures.

In 2024, the CCAMLR failed to agree on new “move on” rules. These would ensure fishing vessels leave an area once they have caught a certain amount, tackling the issues of local depletion. CM 51-07 expired without replacement at the end of the 2024 fishing season, leaving the krill fishery with only CM 51-01 (when 620,000 tonnes of krill is caught, fishing automatically stops) as guidance.

The CCAMLR currently doesn’t have any special measures to prevent the full quota being taken from the same place.

What is next in the Southern Ocean?

The krill fishery isn’t just dealing with changing policies, but also a changing Ocean.

The Southern Ocean is getting warmer.

The areas of sea ice coverage are decreasing, and a record low in 2023 was 1.02 million square kilometres less than the 1979-2022 average daily minimum. That is the same size as Egypt. The previous four years have seen the minimum sea ice extent drop below 2 million square kilometres.

Krill depend on sea ice. The changing amounts of ice impact the krill’s food – phytoplankton. As juveniles, they stay close for protection and graze off the algae that can grow on it. Less ice means less shelter and less food, which leads to a lot less krill before any fishing has happened. Maximum sea ice extents impact the following summer blooms of krill – more ice means more food and shelter for young krill, who then visibly blossom in the summer. 2025 had the third lowest sea ice maximum, behind only 2023 and 2024.

Since the 1970s, we have been seeing a reduction in the density of krill adults, and in the occurrence of very dense swarms around the Antarctic peninsula. These environmental changes also mean the krill are moving south – staying closer to the pole, where it is colder. This means that the northern ecosystems are losing access to their main food supply. It also means the areas divided up for krill fishing may not capture where the krill are anymore.

One of the biggest wins for nature and conservation is the return of the whales.

After population depletion by industrial whaling, whale populations are increasing to their historic levels. As whales return, the amount of krill they eat increases.

Acceptable krill catch limits from 20 year ago may no longer cater for the larger whale populations, which is why re-assessment is so important.

Even if the amounts of krill taken are acceptable, the fishing vessels can still affect the whales. The vessels disturb the whales and can spread krill swarms out more. This means that whales can spend more energy getting the same amount of food, which decreases their body condition and reduces their capacity to reproduce.

The situation gets more complicated when you combine the changes. Less krill is likely to disturb the recovery of whale populations.

Where do we stand on the future of krill?

The warming world and returning whales need to be factored into our management of krill fishing. But recent progress has been slow.

There is a lot of disagreement over the future of the krill fishery. In the meeting of the CCALMR in October 2025, Norway proposed a doubling of the catch limits for krill. At the same time, scientists are calling for a re-evaluation of the limits, as they are based on old data and assumptions. Meanwhile, concern about the exploitation of the Southern Ocean resulted in UK retailer Holland and Barrett withdrawing all krill products by April 2026.

The challenge of consensus

The CCAMLR operates on a consensus decision making model. Everyone has to agree before new measures can be introduced. New MPAs haven’t been agreed because one or two countries have blocked them on the grounds of a lack of scientific evidence and their right to fish for krill and other target species.

What have we learned from exploitation in the Southern Ocean?

There is a lot of hope to be found in the Southern Ocean. Fur seals were given protection in 1909, and their numbers have now recovered to over 3 million. Whaling stations on South Georgia are relics of the past, rusting microcosms of the industry they supported.

The CCAMLR is different to any other fishery. It has learned from previous mistakes and has made decisions based in robust science. A well-managed fishery will always be called too conservative, too limiting, too safe, because it will never reach the point of collapse or decline. So far, krill populations have remained steady, unaffected by us.

The Southern Ocean is changing, and so the fishery must change with it. Climate change, more whales and improved understanding of the ecosystem should all be considered in new fishery management. There are three things to take from this:

- We are capable of facilitating the recovery of the Ocean.

- The Southern Ocean, and its krill, are facing new challenges.

- We all benefit from the Southern Ocean, and its krill, flourishing.

Krill are small but mighty. They fuel giants and balance our climate. The continuing battle to protect them demonstrates how far we have come. We can understand better than ever the benefits this tiny crustacean imparts as a part of its ecosystem.

We don’t have all the answers, but the progress is reassuring. A relationship with the Ocean that is based in our understanding of the impacts of our actions will be much more productive than one based on the potential profits.

Krill are not the impressive, charismatic Ocean animals that whales and penguins are. But if we fail krill, we stand to lose the rest. Krill can be the species that marks a new chapter in our relationship with the Ocean – one in which we work with our Ocean rather than at the cost of it.