- Science: Explained

What Happened to the Steller’s Sea Cow? Explained.

There are two theories about what happened to Steller’s sea cow. Let’s unpack them.

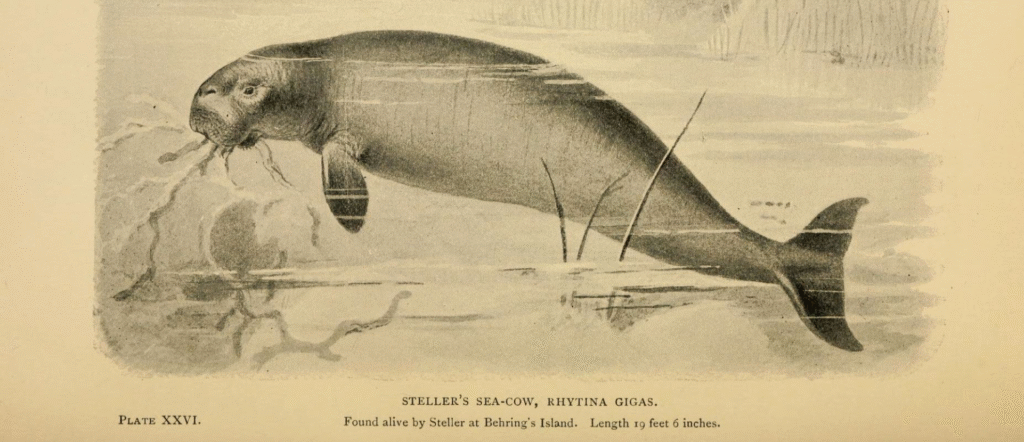

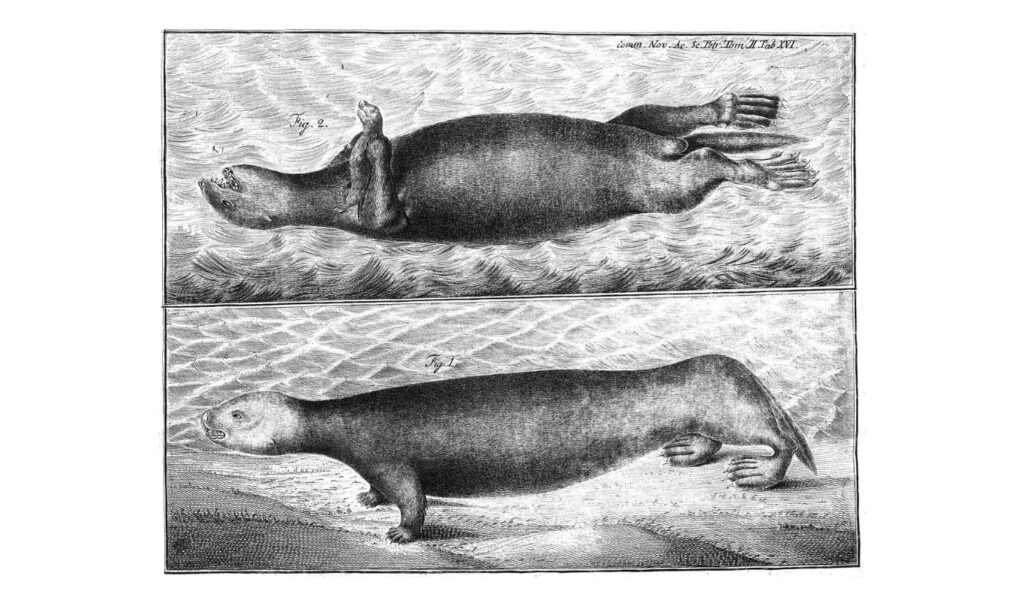

Steller’s sea cow was a 7-metre-long, 5-tonne cousin of the manatee; known to graze peacefully in kelp forests. But just 30 years after the sea cow’s discovery – it vanished from the Ocean forever.

In this article we’re going to explore two theories for why this marine species disappeared. Both involve hunting, but one requires an understanding of the habitat that Steller’s sea cow called home: the kelp forest.

By looking at this complicated history, we can begin to understand the complex interactions going on under the Ocean surface, and learn lessons about how we can best preserve these incredible ecosystems in the present.

The story of Steller’s sea cow starts with a shipwreck.

On the 6th November 1741, the Svyatoy Petr was shipwrecked on an isolated and uninhabited island, now known as a part of the Commander Islands chain. For several months, the crew of sailors, cartographers, geographers, and natural historians had been carrying out one of the first scientific explorations of the North Pacific.

Stranded for nearly a year, the remaining crew salvaged materials from the wreckage, and built a ship that could cross the Ocean back to Russia.

One of the most consequential outcomes of this failed expedition was the presence of a curious and observant naturalist, George Wilhelm Steller. For almost a year, he made meticulous observations, sketches, and notes on the unfamiliar and captivating wildlife that surrounded him, which have been left to us as an invaluable historical and ecological artefact.

From a massive population to extinct:

One creature left a particularly strong impression on George Steller. He wrote in his journal of ‘gigantic manatees grazing all about the island’s lagoons’. These cousins of the manatee would often exceed 5,000kg in weight. He observed that they were very sociable creatures, sticking in large herds and eating kelp floating at the Ocean surface as though it were grass, ‘in the same way as horses and cattle’.

Although Steller wrote that they were so numerous that ‘that they would suffice to support all the inhabitants of Kamchatka’, a twist of fate left them extinct by the 1760s. To understand them, scientists have had to look at historical evidence and their closest living relatives, dugongs and manatees.

Story One: Hunting

Steller’s crew hunted sea cows as a source of food whilst stranded on Bering Island. Steller recalled a story in his journal about the psychological stress this placed on them. Whilst hunting a female sea cow, a male aggressively followed and tried to ram their boat, following all the way to shore long after the female had died. They also hunted other creatures including otters and seals.

This is the most common theory for the extinction of the sea cow: they were exploited for their meat, fat, and hides, the latter of which would be used in the construction of boats. This theory suggests that the hunting was so widespread and unsustainable that the population was put under great stress and collapsed within 30 years.

Story Two: Loss of Keystone Species

In the past few decades, a group of scientists have put forward an alternative theory.

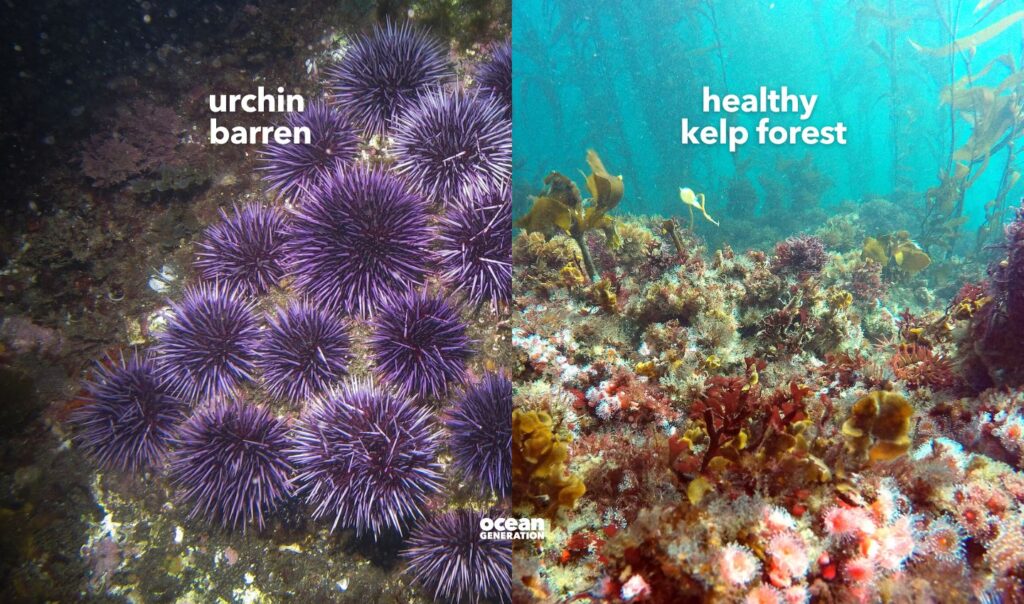

This theory pays attention to the complex dynamics of kelp forests, and the role that sea otters play as ‘keystone species’: species that play a disproportionate role in managing the ecosystems they call home. As we explained in a recent article, sea otters’ appetite for sea urchins prevents overgrazed ‘urchin barrens’ emerging – desolate stretches of rock with little to no vegetation – in the place of lush and biodiverse kelp forest. Do read this article if you want to learn more!

Whilst Steller’s sea cows were hunted on these expeditions, sea otters were the main pursuit. When the first groups returned with the fur pelts of sea otters, traders were so astonished at their thickness and quality that they sold for nearly 100 rubles a pelt – 25 times more than the equivalent pelt from land animals. It’s been said that they were, at some points, worth more than gold! In the wake of the euphoria that ensued, the sea otter population collapsed so quickly and dramatically that they were observed to be at the brink of extinction around the Commander Islands by 1753.

Kelp forests create a complex habitat for a diversity of species, with one study in Norway suggesting that the average piece of kelp in their study site supported 8,000 individual organisms. If sea otters are lost to hunting, the kelp forests can be transformed into urchin barrens, as there are no otters to control sea urchin populations. As kelp is lost, the Steller’s sea cow loses their source of food, a change to their environment that might have ultimately resigned them to extinction.

Which theory about the extinction of Steller’s sea cow is it?

Both theories are reasonable. Ecosystems are complex and difficult to understand completely, and it is probably a bit of both. As I have been reminded by one of the scientists who proposed the second theory, ‘the lack of good data from the extinction of sea cows means that we are unlikely to ever really know.’

Sea cows may be extinct, but this story is not irrelevant, and shouldn’t be the cause of doom and gloom or eco-anxiety.

As scientists have better understood the role of sea otters as a ‘keystone species’ that maintain kelp forests, we have become more capable of putting conservation programmes in place that work. The recovery of sea otter populations in the Pacific is arguably one of the greatest success stories of conservation, bringing back both populations of sea otters and the coastal ecosystems they engineer such as kelp forests. At the moment, we can look to innovative projects such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s surrogacy programme for hope, which raises orphaned pups so that they can be reintroduced back to the wild. (You can see them on the aquarium’s live stream here!)

We may have lost Steller’s sea cow, but we can still restore kelp forests for the countless other species that call it home.

Steller had a sense for the value of sea otters, though he may have primarily seen them as creatures to hunt. He even wanted to bring some home as pets. ‘The sea otter,’ he wrote, ‘deserves the greatest respect from us all’. Although he couldn’t have understood the complex work that they do as a ‘keystone species’ as we do today, we can all wholeheartedly agree with him.

Cover image via Biodiversity Heritage Library